复制的回响:数字艺术史与作者论危机

(1. 香港浸会大学创意与艺术学院电影学院, 香港 999077

2. 北京大学图像学实验室, 北京 100871)

摘要: 数字化进程在引发本体论危机并激化学科话语之辩的同时,作为一种方法论框架和生成性力量,正在重塑知识生产的本质及历史书写的方式。本文探讨了艺术史数字化过程中涌现的多元实践,包括数据库迁移、计算辅助分析、文本与话语的流动以及日益影响学术生产的算法重写与人工智能生成。在数字技术生成海量细节的同时,算法运作却使话语游走于解体的边缘,从而对长期以来的学术范式与等级体系形成挑战。本文以“复制”作为隐喻线索,深入探讨在数字艺术史中重构真实性与主体性的必要性。通过重新定义谁拥有书写的权利,谁在新的数字范式下掌握知识生产的权威,历史叙述如何建构与重构,以及知识通过何种机制得以生产、传播和合法化,本文指出,数字艺术史正逐渐脱离传统史学的轨迹。最终,从学者与学术机构到算法与数据基础设施,人与非人的交织互动,将从根本上重塑围绕艺术、媒介、技术与信息展开的协商机制。

关键词: 数字艺术史, 数字化, 作者论, 主体性, 真实性, 算法

引用格式: 陈璐. 复制的回响: 数字艺术史与作者论危机[J]. 艺术学研究进展, 2025, 2(1): 139-156.

文章类型: 研究性论文

收稿日期: 2025-02-11

接收日期: 2025-02-14

出版日期: 2025-03-28

1 Introduction

“A book has neither object nor subject;it is made of variously formed matters,and very different dates and speeds”[1].This evocative statement from A Thousand Plateaus resonates deeply with the challenges facing contemporary art history.In an age where artworks dissolve into hybrid data streams,where authorship fragments into algorithmic agencies,and where narratives proliferate across decentralized networks,traditional art historiography — once firmly rooted in material specificity,linear chronology,exclusive authorship,and fixed formal/stylistic/ideological analysis—struggles to account for the fluid,networked,and computationally mediated practices within digital culture.Deleuze and Guattari’s statement,originally proposed to elaborate on the rhizomatic—non-linear,networked,and polycentric—mode of thinking,challenges linear and hierarchical epistemologies[1].Subversive for art history and any knowledge-producing discipline,this philosophical concept allows us to re-examine the evolution of the object of study from multiple and intersectional perspectives.If art historical narratives can break away from linear chronicles while freeing themselves from a research focus dominated by a singular theoretical perspective,they can instead explore complex networks of interpenetration between different art genres,revealing the neglected heterogeneity and diversity of art history — precisely what digitization has brought to the table.

This study adopts the concept of“copy” as a dual analytical framework.On one hand,digital replication and reproduction are not merely technical processes in the digitization of artworks—the very objects of art historical research—but also sites of tension where questions of reliability,authenticity,materiality,and subjectivity are destabilized.Whether through high-resolution imaging,3D modeling,or AI-generated restoration,the act of copying raises critical issues:What is preserved,altered,or lost in translation? These questions do more than challenge established historiographical traditions—they reshape the focus and methodology of art historical writing.As artworks lose their singularity and details become infinitely reproducible,the dissolution forces scholars to rethink what to write,how it is written,and by whom.Consequently,new research frameworks—such as computational analysis,digital reconstructions,and algorithmic historiography—have emerged,fundamentally altering the dynamics of authorship in art history.

On the other hand,the“copy” transforms the very act of writing art history by challenging scholarly authorship and its traditional hierarchies.In the digital landscape,replication,reinterpretation,and algorithmic mediation blur the line between scholars and the public,turning all into contributors rather than distinct authors.Meanwhile,practices like crowdsourced data annotation,participatory archives,and AI-generated content fragment established modes of criticism and historiography,dispersing art historical discourse across digital platforms.As scholars increasingly act as facilitators rather than just creators,the question shifts from who writes art history to who truly shapes its narrative,as authorship becomes entangled with evolving discursive practices,power structures,and technological infrastructures.

Through this lens,the paper critically examines the renewal of art historical methodologies in the digital age and interrogates the ontological and epistemological challenges emerging from this evolving landscape.As Rodríguez-Ortega(2019)argues,digital art history has experienced more than a mere epistemological shift;it has witnessed a fundamental transformation.He states,“We should be asking ourselves how the intellectual mechanisms that we have used to construct art-historical knowledge(comparison,observation,establishing similarities and differences,classification,relationships,etc.)change when they are carried out by using machines,algorithmic calculations,and lines of code” [2].Within this evolving landscape,art historical discourse is no longer solely authored,interpreted,and validated by professions but is instead shaped by an expanding network of human and non-human agents,including computational processes that govern data visibility,platform logic that curate narratives,and algorithmic infrastructures that determine what is recognized as historically significant.Further,rather than treating digitization as a neutral extension of traditional methodologies,this study situates it within broader discussions of technological mediation,artificial intelligence(AI)ethics,and the politics of cultural memory.In doing so,it offers a framework for understanding the interplay between human,nonhuman,ideology and the digital infrastructures that may shape a posthuman future.

2 Digital Art History:Debates Beyond the Digital

Traditional art historiography has long beengrounded by a set of core paradigms:material specificity,linear narratives and chronological frameworks,exclusive authorship,and established formal,stylistic,and ideological analytical methods.These frameworks are reflected in the work of early theorists such as Heinrich Wölfflin,whose formalist approach laid the groundwork for systematic stylistic analysis,and Erwin Panofsky,whose iconological methods endeavored to decipher the symbolic dimensions of art.Yet,even as these paradigms provided a seemingly stable foundation for inquiry for years,they also bore intrinsic limitations.Aby Warburg’s groundbreaking work—exemplified by his Mnemosyne Atlas—disrupted the rigid chronological ordering of art history by foregrounding cultural memory and non-linear,associative interpretations.More recently,Fredric Jameson has critiqued these traditional models by exposing the socio-political logics underpinning conventional historiographical practices[3].Exactly as postmodern deconstructive ideas gain prominence,it becomes increasingly clear that the paradigms sustaining traditional art history are not immutable truths but historically contingent constructs,and they have become almost incapable of keeping up with the changes in emerging media forms.Whereas,the rise of digital technologies has not merely extended these models but has fundamentally reconfigured them,subjecting them to intensified epistemological challenges.

While technological interventions in art historical research—ranging from early digitization initiatives to computational cataloging—have been underway for decades,the recognition of digital art history as a distinct field of inquiry emerged only recently.It was not until 2013 that Johanna Drucker offered a comprehensive definition and incisive critique of digital art history(DAH),firmly establishing it as a critical area of study.Drucker provocatively asserts “digital methods change the way we understand the objects of our inquiry” [4].However,early digital projects,confined largely to the migration of archival materials—a phase Drucker labels “digitized art history” — focused on migrating existing art histories to digital repositories,reproducing existing categorization frameworks rather than questioning them.Emphasizing that “digitization is not representation but interpretation”,Drucker calls for a reassessment of how computational methods redefine the identity,purpose,and dissemination of art historical knowledge[4].Although Drucker was among the first to anticipate how the rapid advancement of digitization would provide art history with an expanded methodological toolkit,her proposed methodological frameworks now appear insufficient to fully account for the disruptive transformations that digital technologies continue to impose on the field.

Paul Jaskot critiques Drucker for implicitly naturalizing both the subject of art history—by centering it on the meaning of individual objects—and the methodological approaches inherited from poststructuralist traditions,argues that digital art history is not merely about adopting new computational techniques but about redefining the discipline’s core intellectual concerns[5].In contrast to Drucker,Jaskot situates digital art history within a broader historiographical tradition of methodological debates,emphasizing that its significance lies not only in the technical affordances it offers but also in its capacity to interrogate and reshape the critical questions underlying art-historical inquiry.He further contends that digital art history presents a radical opportunity to extend and reframe these established subjects and methods rather than merely applying digital tools to pre-existing paradigms.To further illustrate its transformative potential,Jaskot identifies four key methodological areas that extend beyond mere technical adaptation:digital storytelling,which enables dynamic,interactive art-historical narratives and public engagement;text-based corpus analysis,which facilitates linguistic and semantic investigations of art-historical discourse;network analysis,which visualizes relationships between people,objects,and institutions through weighted connections;and spatial analysis,which employs digital mapping and 3D modeling to reconstruct historical and cultural contexts[2].These approaches underscore the field’s ongoing negotiation between computational affordances and traditional historiographical concerns.For instance,the increasing convergence of cloud storage,artificial intelligence,algorithmic curation and large-scale data-driven research methods not only forces researchers to adapt to the new methodological apparatus of art history as quickly as possible,which in turn ideologically reconfigures the foundational premise of the discipline,i.e.What should be included in the field? Who holds the right to write? What knowledge will be produced? In this sense,digital art history emerges not merely as an extension of existing narratives but as a promising research filed on its own right—raising critical questions about which narratives,actors,and analytical frameworks are privileged in the digital turn.

Expanding on this critique,Rodríguez-Ortega asserts that the digital turn in art history fundamentally alters the conditions of knowledge production.He warns that any critical perspective is inevitably mediated by computational processes and data visualizations,which do not simply reveal hidden truths but actively construct their own realities through the act of analysis.Consequently,the rhetoric of “discovery” associated with digital methodologies risks fostering the illusion that data-driven insights merely uncover pre-existing knowledge rather than generating entirely new interpretive frameworks[2].Given this,he urges scholars to rethink the core problems of digital art history in what he describes as the post-digital age—an era in which humanistic thinking can no longer be taken as the sole point of reference.He calls for a reinvention of how ideas,theories,and concepts are produced,distributed,and circulated,emphasizing that digital art history now operates within a hybrid ecology where human agency is no longer central but is instead enmeshed with algorithmic systems and non-human actors[2].

Together,bothJaskot and Rodríguez-Ortega’s reconceptualization present profound methodological and theoretical challenges to DAH.If digital tools do not merely enhance traditional scholarship but fundamentally reshape the mechanisms of interpretation and meaning-making,art historians must critically examine the epistemological frameworks that these technologies construct.For example,Klinke points out that encyclopedic databases of images—whether physical or digital—do not inherently constitute critical scholarship suggesting that art historians must engage in data critique to avoid reproducing biases inherent in algorithmic processing[6].Näslund and Wasielewski’s critical note that the historiographical paradigm underlying the DAH is far from neutral furthers the concern.They argue that computational techniques,often assumed to be objective analytical tools,are deeply embedded within historical,institutional,and political biases that shape not only the datasets used in digital art history but also the processes by which knowledge is produced,structured,and interpreted[7].

Overall,these debates reveal a profound disciplinary reckoning,one that predates the digital era yet has been radically transformed by the digital.As scholars confront the implications of DAH,the field stands at a critical juncture,not only in terms of integrating new technologies but also in rethinking the role of human agency in knowledge production.The complex interplay of human and technological forces,which long discussed in posthumanism,digital humanities,technology philosophy,and AI ethics,challenges conventional assumptions regarding authorship,expertise,and the construction of historical narratives.Consequently,the adoption of digital methodologies must go beyond mere technical implementation and include a critical interrogation of the epistemic frameworks that govern digital knowledge production and its broader implications for the discipline.In this context,human subjectivity remains both the central challenge and the key to addressing these issues,underscoring that even in a digitally mediated era,the capacity for critical reflection and interpretive agency is indispensable.By exploring how authorship is reconfigured within this dynamic landscape,this study aims not only to contribute to the development of art historical discourse but also to the broader critical debate of redefining the position of the human being in an era increasingly shaped by computational and algorithmic processes.

3 Copy as Crisis,Copy as Genesis

The entanglement between digitization and replication technologies can be traced back to the simple “Ctrl+C/Ctrl+V” command.However,as technology continues to advance,this act no longer fully captures the complexity of how artworks are reproduced,transformed,and disseminated in the post-digital era.Reproduction has shifted from a deliberate,finite,and isolated operation to an automated,continuous,and large-scale process,deeply embedded within the infrastructure of DAH.From the replication of artworks in high-resolution archives to database migration,computationally assisted analyses,algorithmic curation,AI-generated synthesis,etc,the acts of copying have become both omnipresent and inescapable.As art history migrates into digital space,images,which have long at the core of visual culture,have borne the brunt of this transformation.

Launched in 2011 by the Google Cultural Institute,Google Arts & Culture(GAC)collaborates with museums and cultural institutions worldwide to digitize and provide high-resolution access to artworks.Using technologies such as Gigapixel imaging and AI-driven metadata tagging,GAC extends the democratizing tendencies of mechanical reproduction identified by Benjamin[8],yet simultaneously reconfigures replication through algorithmic logic,modular data structures,and interactive engagement.As Harald Klinke demonstrates,the advent of Big Image Data does more than expand available visual content—it restructures the interpretive paradigms by which artworks are understood,introducing a crisis that challenges established criteria of authenticity and epistemic authority[6].

For Klinke,Big Image Data(BID)refers to the vast and diverse corpus of digital images that are generated,collected,and processed in the digital sphere.It is not simply about the large volume of images but also encompasses the variety of visual information and the dynamic processes used to extract,analyze,and interpret these images.For example,while Panofsky emphasized the layered interpretation of images in a historical context,BID allows for large-scale visual pattern analysis beyond human capacity,given that BID includes both the “low-level features”(such as pixel values,brightness,hue,and saturation)that computers can easily quantify,and the “high-level features” that convey semantic and cultural meaning — a gap that remains challenging to bridge through purely computational methods[6].More importantly,BID does not replace human interpretation;rather,it creates new possibilities for distant viewing,where macro-scale trends across image datasets can be analyzed in ways that were previously impossible.

Likewise,in the case of the GAC,it never stopped at being an accessibility device,nor was it simply a tool to reshape the way artworks are catalogued,compared and understood.It is thereby an active force shaping the way we perceive and engage with art.For instance,the ultra-high-resolution images allow viewers to zoom in and observe details invisible to the naked eye—such as the fine cracks in Van Gogh’s brushstrokes(see Figure 1),the particulate pigments in Leonardo da Vinci’s Sfumato,or the delicate weave of centuries-old canvas fibers.This form of reproduction is not a duplication but a hyper-realistic reconstruction that challenges conventional notions of materiality and technique in art history.Rather than replacing the original,these digital renderings create a parallel form of existence,one where the artwork’s “aura”[8] is not necessarily lost but instead renegotiated within a computational and networked context.

Fig.1 Detail views of a high-resolution Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night

In fact,the relationship between reproduction and origin has long been a central concern in both philosophy and art historiography.Does the copy diminish or extend the truth of the original? In his essay,The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction(1936),Walter Benjamin argues that mechanical reproduction technologies,such as photography and film,strip artworks of their unique “aura” — the distinct cultural,historical,and mystical value that an original artwork holds.This loss of aura then diminishes the artwork’s authenticity and societal significance[8].However,Benjamin also highlights that this shift allows art to reach a broader audience,making it less an elitist experience and more a political,public phenomenon.Despite the loss of the aura,Benjamin suggests that mechanical reproduction opens up new opportunities for critical creation and innovation,allowing artists to engage more directly with societal issues and contribute to political and cultural change.Further,Jean Baudrillard posits that technological mediation has severed the referential bond between representation and reality,replacing it with a self-referential system of simulacra.In this hyper-real paradigm,copies no longer trace back to an original “reality”;instead,they proliferate as autonomous signifiers,generating new realities through algorithmic iteration and digital dissemination[9].Here,the “reality” of art becomes contingent on its circulation within digital ecosystems rather than its ontological “truth” grounding.

This condition finds a striking parallel in digital art history,where the boundaries between material authenticity and computational replication are increasingly blurred.Klinke cites W.J.T.Mitchell’s term “meta-image”[10],stating that “A digital image is not simply an image—it is a meta-image that contains structured data,analytical information,and relational links,allowing for new ways of engaging with and interpreting visual culture” [6].To put it differently,art history based on the “meta-image” is no longer governed by a vertical chain of “original-copy” but unfolds as a network of horizontal differentiations driven by user clicks,collections,and shares.When a fifteenth-century manuscript is fragmented into metadata and recombined into a searchable database,when a Song Dynasty painting is algorithmically transposed into an Instagram filter,or when blockchain authentication creates a digital provenance system for entirely virtual artworks,art historical discourse is no longer grounded in stable objects but instead circulates as fluid,iterative data flows.

Furthermore,not any medium of art is inherentlyoverwhelmed by digitization.Beyond visual arts,the materiality of other art forms within DAH becomes a complex issue.Physical artworks cannot be entirely separated from their material context when rendered digitally;rather,they risk being reduced to mere symbols or data points.For example,when it comes to music,dance,conceptual art,or performance art,does the process of digitization flatten these non-physical art forms into videos or just code? Moreover,the replication of art now extends to works that lack a conventional original altogether—such as AI-generated contents.This shift emphasizes the critical need for robust methods to annotate these creations and define their authenticity:while such images may exist as data in their own right,their necessity and significance for entry into art historical writing remains an unsettled consideration.

Fig.2 Juxtaposing Dunhuang murals with Picasso’s Cubism

As Anderson[11] notes,“Information technologies—for better or worse—have undeniably altered the way historical data is captured,processed,and disseminated.” Digital reproduction,therefore,does not merely replicate the original;It actively reshapes historical narratives through the design of database structures,visualization tools,and algorithmic frameworks.The process of digital mediation directly influences whose version of history is constructed and preserved.Under these conditions,authorship becomes a negotiated concept,shaped by a mediating interface,infrastructure,and information.The question of what is considered “authoritative” thus is dependent on the visibility of metadata and algorithms that determine which accounts gain prominence.

In addition to the ability to click through by Artists,Mediums,Art Movements,Historical Events,and Historical Figures,users of GAC can break away from traditional art historical frameworks by exploring through channels such as Explore by Time and Color,Themes,and Popular Topics,or even algorithmic by “Style Similarity.” For example,juxtaposing Dunhuang murals with Picasso’s Cubism(see Figure 2)based on its “database logic” [12].This rhizomatic,non-linear,yet exhaustive historical information,along with the juxtaposition and comparative analysis of artworks across eras and regions,may therefore reshape our understanding of both individual artworks and artistic concepts.However,as Udell(2019)highlights,while the GAC offers unprecedented digital access to millions of artworks,it functions primarily as a “content museum” —a vast repository of digital objects rather than an interactive or interpretive space.The platform’s “infinite scroll” design encourages casual browsing over deep engagement,exacerbating concerns about data overload and the algorithmic structuring of historical knowledge[13].Moreover,its classification system,based on Western taxonomies,frequently miscategorizes non-Western artworks,revealing implicit deficiencies and even biases in the algorithms.For example,indigenous art from Africa and Australia is often classified under broad “folk art” categories,stripping these works of their specific cultural and historical contexts[13].Jaskot situates digital art history within a broader historiographical tradition of methodological debates,emphasizing that its significance lies not only in the technical affordances it offers but also in its capacity to interrogate and re-conceptualise key issues in art historical research[5].Whilst the idea of BID and digital practices such as GAC challenge traditional privileges and hierarchies—expanding access to large visual datasets for both professionals and non-professionals—they also paradoxically highlight some of the fundamental challenges inherent in digitization.Before this,concerns long been centered on the diminishing distinction between the original and its replica when artworks are digitized.Prior to this,a longstanding concern centred on the distinction and identification of authenticity when artworks are reproduced.When scanning technology allows for infinite amplification of detail,the distinction between the original and the copy becomes subtler than ever,thus potentially devaluing the notion of the original and subverting the power structure between the original and the replica.As the digital transformation goes forward,more profound questions arise:

(1)Reliability of Digital Technologies.Despite the continued efforts of institutions to establish their digital archives,deeper challenges persist:the inherent interpretability of digitization[4].As cloud storage capacity and replicability continue to expand,knowledge and information become increasingly boundless.However,their authenticity and reliability seem to grow more detached from their original source,the artwork itself.Defining a “complete” work becomes more challenging when the artwork is transformed into a synthesis of data and information about the artwork and its context.As Jaskot reminds us,digitization is a “problem of mediation.” [5] For instance,when data is lost or misaligned,the digital version may struggle to retain its authenticity and legitimacy.Additionally,in an age of unlimited storage,an ensuing question is whether knowledge and information can be considered infinite.Anderson cautioned that even searchable databases “may not adequately represent or make available the range of materials they contain”,thereby emphasizing the inherent limitations of digital infrastructures and their access channels[11].This raises fundamental concerns about who controls and accesses these vast data repositories—who can access,modify,interact with,and ultimately wield the power to overwrite the historical record.The proliferation of copies and code demands a critical interrogation:when art history becomes editable code,calculable pixels,and trainable models,does “author” remain a meaningful concept within the broader system of replication?

The“post-digital”[2] condition further complicates this landscape.NFTs,for instance,present a potential solution to the challenges of digital authentication and provenance.By embedding an artwork’s metadata and historical context into the blockchain,they promise a more secure method of verifying authenticity and ownership.However,their emergence also underscores the inherent instability of digital artworks,which simultaneously exist as code,images,and speculative assets.As Pawelzik and Thies observe,“there will be no possibility at all that one can tokenize a copy of a work” [14],emphasizing the unique challenges of preserving originality within the NFT space.Moreover,their practical application remains limited;not all artworks lend themselves to tokenisation,and legal complexities,such as copyright,further complicate their adoption.

At the same time,the increasing transparency of historical details introduces complex epistemological and political questions.Digital archives,often perceived as neutral repositories of knowledge,are in fact shaped by the technological and institutional frameworks that create them.Scholars such as Manovich have argued that the digital reconstruction of historical data inherently involves selective processes that mediate and sometimes distort our understanding of the past[12].This implies that digital reproduction does not simply erode the aura of artworks;it also enables the migration and transformation of that aura across different contexts.This is not Baudrillard’s concept of “simulation”(simulacrum),but something subtler that requires us to recognize the interconnections between the various forms of digital art and the blurred boundaries between creators,artworks,and audiences.Rodríguez-Ortega points out that in the post-digital society,digital and non-digital are no longer opposing elements but instead present a complex state of hybridity and fusion,which demands the development of a “critical digital art history”,going beyond simplistic,positive,or inevitable responses to the “technological revolution” [2].

(2)Subjectivity and Human Agency in Digital Art History.The integration of both human and nonhuman factors—including infrastructures,programming languages,and algorithmic systems—requires a reassessment of subjectivity in art history.The tension between technological potential and established methods brings to light a fundamental question:can the humanistic traditions of art history survive the shift toward “digital art history,” and if so,how will they adapt? At the same time,the digital environment alters the role of human agency in shaping knowledge.Users are no longer merely passive recipients of information but increasingly assume the role of data managers—curating,controlling,and interacting with digital content.

For instance,when artificial intelligence is employed to reconstruct missing sections of Dunhuang murals,art history transforms into a layered,rewritable palimpsest—a dynamic space of human-machine collaboration.In this collaborative interplay between human creativity and machine learning,the distinction between creator and audience grows increasingly blurred,giving rise to new models of authorship and authority.However,as machine intelligence becomes ever more sophisticated and predictive,how should we balance and integrate the intellectual contributions of both human and non-human participants? In this evolving landscape,human agency may itself be redefined as a machine collaborator—one that actively manages,interprets,and adapts digital representations,ultimately shaping a new form of subjectivity.

(3)Snackable Content.With the dramatic expansion of available information and resources,copying has evolved beyond a purely institutional practice into a complex,multifaceted process.It now encompasses collation,manipulation,and reinterpretation,engaging individuals at all levels in the creation and transformation of knowledge.This transformation is particularly evident in the rise of “snackable content” [15],a form of highly condensed,easily digestible content designed for rapid consumption on platforms like TikTok,Bilibili,and Instagram.These short-form videos and posts often present quick overviews of famous paintings,simplified narratives of art movements,and even meme-based reinterpretations of art history concepts.While such formats make art history more accessible to broader audiences,they also raise concerns about the loss of depth,context,and critical engagement.With algorithms prioritizing content based on engagement metrics rather than academic accuracy,historical narratives have the potential to be shaped not by academic discourse but by this snackable and extremely efficient viral distribution.In this sense,the history of digital art,shaped by this algorithmically filtered dynamic and the prioritization of “snackable content,” will have increasingly blurred boundaries with commerce and entertainment.As Bernard Stiegler argues,tertiary retention—the process through which human knowledge is accumulated,transmitted,and reconstructed—has been central to the development of culture and thought[15].Traditionally,this process was mediated through human-controlled external supports such as books,archives,and physical artifacts.However,with the rise of digital technologies,tertiary retention is increasingly governed by algorithmic systems and corporate-controlled platforms,such as search engines and social media.This shift not only alters how knowledge is stored but also reshapes the very nature of subjectivity itself.As memory production becomes influenced by technological infrastructures,it challenges traditional forms of agency and the role of individuals in shaping and understanding their own cultural memory.The boundaries of what constitutes individual knowledge and historical understanding are increasingly determined by external,algorithmic programs.

In sum,digital reproduction is more than just atechnical process of digitizing artworks,or a simple relocation of traditional art history to digital space,but a deeper ideological process of self-renewal.In this process,the issues of reliability,authenticity,and materiality will be reconfigured,both in terms of artworks and the mechanisms and subjects of historical writing.The process of digitization has not only challenged the methodologies of established historiographical traditions,but has also given rise to new research frameworks such as computational analysis,digital reconstruction,and algorithmic historiography,which have fundamentally altered the boundaries of art history.These shifts have reinvented the focus and possibilities of art historical writing,requiring us to adapt to new mechanisms of writing,redefining the roles,identities,and positions of human beings themselves,and ultimately giving rise to new forms of authorship.As we will explore in the next section,returning to the essence of art historical knowledge production and dissemination,the process of redefining discourse and knowledge involves a constant interplay of loss and recovery.In this process,the concept of authorship is continually deconstructed and reconstructed within texts and discourses.

4 The Shifting Boundaries of Authorship and Mediated Authority in Art History

Returning to art historical writing itself,the hermeneutic frameworks,narrative methods,and power structures that once defined the discipline have undergone a profound transformation.This transformation is the result of a deepening interplay between digitization and historical discourse.In particular,the rapid development of information technology and machine intelligence over the past few decades,and their adoption by researchers,have fundamentally altered the paradigm of discourse production and knowledge updating.Traditional notions of “authority” and disciplinary boundaries have become increasingly blurred,while authorship has become more fluid and co-constructed.

On one hand,the orthodox definition of authorship is being dissolved.Traditionally,academic discourse has been produced primarily by trained scholars within established disciplinary paradigms,with authorship defined as the solitary creative act of experts,validated through institutional and social recognition.However,as observed by scholars,“We found that the subject matter and topical focus of scholarship in DAH differs significantly from scholarship in Art History or Art Journal”[16].Under the extensive operation of information repositories,recommendation systems,and algorithm-driven dissemination networks,anyone— whether a university professor,an amateur,or even non-human entities(data systems/AI)—can participate in the discussion of art history.More fundamentally,as participatory archives and crowdsourced annotation projects mediate access to art historical content,the boundaries between expert scholarship and public contribution are becoming increasingly fluid.These developments not only expand access to information but also reconfigure the mechanisms by which knowledge is extracted,circulated,and legitimized.No longer solely dependent on academic authority,those engaged with art history are increasingly becoming co-creators,actively shaping and redefining historical narratives through their digital terminals.In this case,the traditional distinction between producer and recipient collapses into an absolutely unified “user-reader-viewer-participant” [2],a virtual subject whose agency is mediated through avatars,usernames,databases,and algorithmic flows.

Thus,our values may shift from a singular emphasis on producing unique,original arguments and texts to recognizing curation as a legitimate form of scholarly activity—one in which authorship lies in the imaginative “assemblage” of multiple discursive threads originating elsewhere,generating argumentation through juxtaposition.

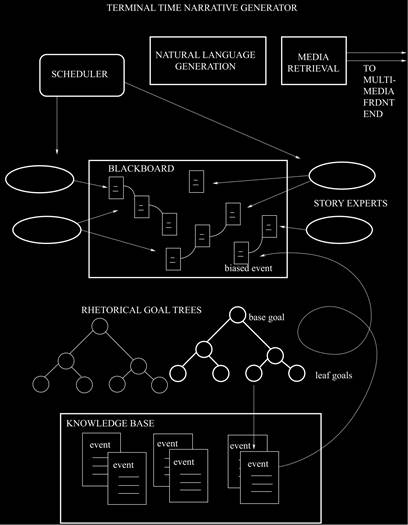

A compelling early example of this transformation is Terminal Time[17].Created by the Recombinant History Project — a collective of artists,computer scientists,and filmmakers — Terminal Time is an AI-based interactive multimedia installation that constructs real-time historical documentaries spanning the past thousand years.Unlike later digital initiatives,such as GAC,which emphasize high-resolution digitization and archival access,Terminal Time posits a radically different historiographical model.As Anderson observes,“Terminal Time further suggests a radical conception of historiography as enabled by digital technology and the proliferation of narratives driven by the logic of databases and search engines rather than the codified conflict-resolution structure of most commercial cinema and mainstream documentary filmmaking.” [11] Functioning as a “history engine,” Terminal Time combines historical events with audience survey responses through artificial intelligence,humorously critiquing traditional historiography by generating narratives that mirror viewers’ ideological biases(see Figure 3).Its tagline,“At long last,Terminal Time gives you the history you deserve!” [11] underscores its commitment to delivering tailored,ideologically charged histories.In a way,Terminal Time challenges the possibility of a singular,authoritative narrative and highlights the dynamic interplay between human agency and algorithmic production.While it remains an early experiment,it reflects a time when the coordination between human action and artificial intelligence or algorithms was far less integrated than it is today.It suggests that the instability of narratives produced by humans is just as significant as that of machine-generated narratives.Moreover,in their coordinated collaboration,the boundaries of the subject of production have become increasingly obscured.

In this sense,the process of organizing and editing history is a kind of curation that produces“assemblages” of meaning through the dynamic interaction and recombination of different elements.As art historical discourse increasingly finds itself mediated by digital infrastructures,scholarship is no longer exclusively the outcome of an isolated scholarly labor;database architects,programmers,and platform operators are increasingly co-authors of art historical narratives.At the same time,the process of writing,curating,and interpreting history is no longer the exclusive domain of the disciplines but rather dynamically fashioned by a network of human and nonhuman agents operating in computational regimes.

Fig.3 Algorithmic mechanism of Terminal Time

On the other hand,the mediated nature of digital art history transcends the limitations of specific media and theories,suggesting that in digital art history,historical and theoretical texts are no longer static cultural objects but dynamic entities that undergo continuous reinterpretation and transformation[18].This dynamic intertextuality resonates with Kristeva’s argument that never a “closed text” [19],indicating that the notion of “textual determinacy” is no longer reliable but instead rapidly updated by fluidity and broader networks of discourse.Features such as version updates,comment functions,and hyperlinks — particularly on platforms like blogs,Wikis,and open-access repositories — allow texts to evolve without erasing their earlier forms.As algorithmic recommendations and machine-learning-driven text generation become more involved,the distinctions between creators and consumers,experts and non-experts,and individual authority and collective input are steadily dissolving.

The democratization of text production is advancing rapidly,with authorship increasingly determined by those who can disseminate texts and temporarily occupy narrative space.In this context,new authority figures have emerged as one of the many players in the algorithmic governance ecosystem.In other words,authorship shifts from a creative act to a managerial one,where the role of the author expands to include navigating platforms,engaging with algorithms,and responding to audience input.As a result,the generation of art history is no longer a top-down knowledge dissemination imposed by institutions,but has shifted to a decentralized and democratized model of dialogue.The boundaries between academic and public discourse are renegotiated,and the intellectual interchange becomes much more than authoritative interpretation,instead it is a collaboration based on synthesis and interaction.Under this new framework,knowledge production became a collective endeavor,with diverse voices and perspectives contributing to the ongoing formation of art historical narratives.

Social media platforms have therefore become a crucial ground for the synthesis and interaction.Slavoj Žižek is a Slovenian philosopher and cultural critic,widely regarded for his work in psychoanalysis,Marxism,critical theory,and film theory.While he is also renowned for his innovative use of social media to share philosophical and cultural knowledge,engaging with a wide audience through platforms like blogs,online lectures,and video essays.For example,his blog demonstrates how a traditional academic figure can bypass academic thresholds and directly engage with a broader audience.His social media account,as well,by promoting participatory dialogue,subverts the traditional unidirectional mode of academic communication,where ideas are continually mixed,contested,and redefined.

In China’s digital landscape,platforms like BiliBili and Xiaohongshu provide intriguing examples.On BiliBili,art history content encompasses not only meticulously crafted works by professional scholars but also a wide array of reposted content,amateur creations,remixes,and even parodic videos,offering diverse perspectives on art history.These user-generated videos range from snackable,three-minute introductions to art movements to more in-depth discussions that blend art criticism with informal commentary,reflecting grassroots engagement with art history that is both interactive and thought-provoking.Similarly,Xiaohongshu fosters a space for users to share personal interpretations and comment on popular artworks,gradually constructing new,often fragmented,and sometimes inaccurate art historical narratives that challenge traditional academic authority.However,we must also acknowledge that,in addition to the positive aspects of participatory creativity,art historical discourse is also striving to cope with new constraints and challenges,driven by multiple processes of change.

These processes,such as appropriation,parody,versioning,evading censorship,fragmentation,and distortion,reshape and transform texts in often harmful ways.For example,the three-minute overviews of art movements mentioned earlier,as well as the images,clips,and memes that go viral on social media,are no longer stable and secure.Instead,they are constantly reworked,recombined and reinterpreted.In this rooted network,meaning becomes fluid,constantly negotiated,and renewed through repetitive,differentiated interventions.As the study of art history itself becomes an object of digital reproduction,the traditional hierarchical divisions between knowledge and information begin to disappear,and the cognitive framework of the discipline is no longer rooted in a single source of knowledge,but rather evolves through the constant fission and reinvention of information and codes.As a result,this open access,remixing,and collaborative creation actively disrupts established systems of knowledge,creating what might be called a “culture in bits” [20] a culture in which the boundaries of expertise,authorship,and authority are constantly being redefined and reconfigured,and in turn laying down many latent dangers of crises that need to be handled with care.

Furthermore,with the development of machine intelligence,AI language models have begun to participate in the generation of art histories.This means,AI is not only capable of generating articles based on existing academic materials,but also of offering new perspectives and insights through the analysis of vast amounts of literature.This phenomenon further blurs the concept of “authorship,” as machines have,to some extent,become “co-authors.” Imagine that we instruct an AI language model(such as ChatGPT)to generate art history content for the year 2026.What mechanism is responsible for generating its responses? And what kind of knowledge will we be receiving?

Additionally,while has to be admitted that diversified AI models have brought numerous conveniences to academic research,the quality and authenticity of AI-generated texts have become a focal point of discussion in the academic community,sparking deep reflections on academic integrity,authorship,and knowledge production.Can AI-generated academic papers and art historical analyses meet academic standards? Can they be considered legitimate research outputs,especially when considering issues such as algorithmic bias,data quality,and the reliability of generated knowledge? Dressen[21] pointed out,digital literacy is not only the ability to understand and use digital tools,but also the ability to critically analyze generated texts.Specifically,when engaging with AI models,scholars must critically examine the evolving boundaries between machine-generated texts and human scholarly creativity.This includes not only assessing the extent to which AI contributes to knowledge production but also addressing the ethical issues of algorithmic influence and confronting the potential erosion of intellectual authority by automated content generation.

Since its publication in 2016,The Ethics of Algorithms:Mapping the Debate,written by a research team from the Oxford Internet Institute and the Alan Turing Institute,has been widely cited and discussed[22].This paper provides a comprehensive analytical framework for algorithmic ethics and has become an important reference in AI ethics.The article outlines six major ethical challenges,including:1.Inconclusive Evidence:Algorithms often rely on statistical correlations rather than causal relationships,which can result in highly uncertain decision-making.2.Inscrutable Evidence:Many machine learning and deep learning models are “black boxes,” making it difficult even for developers to explain the logic behind their decisions.3.Misguided Evidence:The outcomes of algorithms are highly dependent on the training data;if the data itself is biased,the algorithm may inherit and even amplify this bias,leading to further unjust decisions.And 4.Unfair Outcomes,5.Transformative Effects,and 6.Traceability.

McLuhan once described media as an extension of humanity,and digital art history,a discipline fundamentally shaped by technological mediation,embodies this extension.The increasing reliance on digital platforms,algorithmic curation,and AI-driven tools for art historical research raises profound questions:if media is indeed an extension of the human race,what does it mean when machines begin to write our unknown history?Is human knowledge still reliable? Can algorithms and data actually produce new knowledge? Perhaps most critically,do humans still have the authority to write art history? The ethical questions posed by this entanglement are no longer theoretical,but looming realities.Fromplagiarism,where the boundaries were once clearly defined,plagiarism now operates in a more blurred space,with copying,paraphrasing and algorithmic synthesis challenging traditional notions of knowledge ownership.Such that as AI-driven tools increasingly intervene in research and interpretation,scholars must grapple with deeper issues such as data transparency,algorithmic bias,authorial integrity,and the commodification of knowledge.How these challenges are addressed will not only redefine the boundaries of human knowledge agencies,but will also determine the role that digital art history plays in the broader field of media-driven knowledge making.

In sum,with the widespread adoption of digitization and AI technologies,the production of art historical knowledge has evolved into a decentralized,dynamically developing network.This transformation not only impacts the methods of research,writing,and dissemination in art history but also challenges traditional models of“authorship” and “authority,” urging scholars to reconsider long-standing disciplinary paradigms and cognitive boundaries.Knowledge production is no longer confined to individual authors or institutions but emerges through the interaction and feedback of numerous participants during the processes of dissemination,reprocessing,and reinterpretation.In this context,the roles of AI have become more critical.Consequently,the rise of digital art history within this framework prompts a reevaluation of the power structures and human agency governing art historical writing and the evolution of authorship identity.

5 Conclusion:Toward a Digital Art History without Art?

At the fractures of digital art history,we witness an ontological inversion:art itself is no longer the central concern.Instead,how we write and the nature of authorship have become the core issues.This is not a pessimistic prediction of digitization,but a radical reconfiguration of art historical subjectivity — in what has been called the post-digital world,we are forced to ask whether “authorship” has any value at all in a world where art history itself has become an editable code,a calculable pixel,and a trainable model.

Whereas traditional scholarship and authority were once associated with the domination of information and an educational system and a creative genius,these hallmarks of prominence are now being redistributed in a new ecosystem:one where scholarship is no longer merely the product of isolated academic labour;a growing number of database architects,programmers,platform operators,and amateur contributors are becoming co-authors of art historical narratives.

This paper metaphorically applies the concept of“copy” as a digitization process to both the object and subject of art historical research,positioning it as a dual force of crisis and genesis.Through this lens,we explore how art histories have been reproduced,who holds the power to narrate these histories,and what constitutes the truths of art in the computational age.Reproduction technologies,from high-resolution imaging to AI-generated restorations,go beyond mere copying,dissecting works of art into editable data.As material singularity dissolves into infinite reproducibility,traditional notions of authenticity and historiographical emphases are reconfigured,giving rise to computational analysis and algorithmic historiography as emerging methodologies.Algorithmic curation,participatory archives,and AI-generated contents are therefore further decentralize authority,transforming art history into a collective process in which scholars,the non-professions,the public,and machines co-create the histories.The question shifts from “who writes” to “what governs knowledge production” — a convergence of platform logics,crowdsourcing interventions and infrastructural power.In this context,authorship evolves from solitary creation to networked facilitation,entangled with the technologies that mediate its expression.

Furthermore,the integration of human and nonhuman actors — including programming languages,database architectures,and automated systems — demands that we reformulate art history’s key questions in the post-digital age.As Rodríguez-Ortega reminds us,when “humanistic” thinking is no longer the sole point of reference[2],we must critically interrogate whether the human capacity for critique,which rooted in our finite,embodied knowledge,can continue to offer reliable interpretations amid an overflow of algorithmically mediated “snackable” content.

When thinking about the future of art history,we must ask whether DAH can continue to function as a distinguish field when the subject matter is increasingly mediated by algorithms,codes,and vast data infrastructures.Where,then,do the boundaries of digital art history lie,as art,digital information,media,technology,and ideology become ever more intertwined? This tension opens new epistemological possibilities and hints at a future in which art history may be reconfigured as a post-human,collaborative practice.Here,the negotiations over art,media,technology,and information are not static but dynamic,continually evolving through a dialectical interplay between computational mediation and critical human reflection.

In this complex landscape,DAH is forced to reimagine itself.In Derrida’s words,“the future is necessarily monstrous”[23] — not in the sense of chaos,but in the necessity of confronting unexpected transformations.The future of DAH may be beyond our current imagination,taking shape through the continuous emergence of technological innovations and theoretical breakthroughs,ultimately revealing a completely new landscape.

Conflict of Interests:The author declares no conflict of interest.

[25] 通讯作者 Corresponding author:陈璐,21481814@life.hkbu.edu.hk

收稿日期:2025-02-11; 录用日期:2025-02-14; 发表日期:2025-03-28

参考文献(References)

[1] Deleuze G,Guattari F.A Thousand Plateaus:Capitalism and Schizophrenia [M].Minneapolis,MN:University of Minnesota Press,1987.

[2] Rodríguez-Ortega N.Digital Art History:The Questions That Need to Be Asked[J].Visual Resources,2019,35 (1-2):6-20.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01973762.2019.1553832.

[3] Jameson F.Postmodernism,or,the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism[M].Durham,NC:Duke University Press,1991.

[4] Drucker J.Is There a ‘Digital’ Art History? [J].Visual Resources,2013,29(1-2):5-13.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01973762.2013.761106.

[5] Jaskot P B.Digital Art History as the Social History of Art:Towards the Disciplinary Relevance of Digital Methods[J].Visual Resources,2019,35(1-2):21-33.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01973762.2019.1553651

[6] Klinke H.Big Image Data within the Big Picture of Art History[J].International Journal for Digital Art History, 2016,2:29-30.

[7] Näslund A,Wasielewski A.The Digital U-Turn in Art History[J].Journal of Art History,2021,90(4): 249-266.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00233609.2021.2006774.

[8] Benjamin W.The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction[M].New York,1935.

[9] Baudrillard J.Simulacra and Simulation [M].Ann Arbor, MI:University of Michigan Press,1994.(Original work published 1981)

[10] Mitchell W J T.Picture Theory:Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation[M].Chicago,IL:University of Chicago Press,1994.

[11] Anderson S.Past Indiscretions:Digital Archives and Recombinant History [A].In:Jenkins H,ed.Transmedia Frictions:The Digital,the Arts,and the Humanities[C].2007:100-114.

https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520957695-009.

[12] Manovich L.The Language of New Media[M].Cambridge, MA:MIT Press,2002.

[13] Udell M K.The Museum of the Infinite Scroll:Assessing the Effectiveness of Google Arts and Culture as a Virtual Tool for Museum Accessibility[D].Master’s Projects and Capstones,University of San Francisco, 2019.Available at:

https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/ 979

[14] Pawelzik L,Thies F.Selling Digital Art for Millions— A Qualitative Analysis of NFT Art Marketplaces[C]. In:ECIS,2022.

[15] Stiegler B.Technics and Time,1:The Fault of Epimetheus[M].Stanford,CA:Stanford University Press,1998.

[16] Näslund A,Wasielewski A.Cultures of Digitization:A Historiographic Perspective on Digital Art History[J].Visual Resources,2020,36(4):339-359.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01973762.2021.1928864.

[17] Terminal Time [OL].Available at:

https://www.terminaltime. com/

[18] Fitzpatrick K.The Digital Future of Authorship:Rethinking Originality[J/OL].Culture Machine,2011,12.Available at:

https://culturemachine.net/wp-content/uploads/ 2019/01/6-The-Digital-433-889-1-PB.pdf

[19] Kristeva J.The Closed Text [J].Languages,1968,12: 103-125.

[20] Hall G.Culture in Bits:The Monstrous Future of Theory[M].London:Continuum,2002.

https://doi.org/10.5040/9781472545541

[21] Dressen A.From Digital Literacy to Data Literacy: How Much Digital Literacy Do We Need in the Art History Curriculum?[J].International Journal for Digital Art History,2021,6:5.

[22] Mittelstadt B D,Allo P,Taddeo M,et al.The Ethics of Algorithms:Mapping the Debate[J].Big Data & Society, 2016,3(2):2053951716679679.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951716679679.

[23] Derrida J.The Other Heading:Reflections on Today’s Europe[M].Bloomington:Indiana University Press,1992.

The Copy Writes Back:Digital Art History and the Crisis of Authorship

(1. Academy of Film, School of Creative Arts, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong 999077, China

2. Image Lab, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China)

Abstract: Digitization process,while provoking ontological crises and fueling debates over disciplinary discourses,has simultaneously become a methodological framework and a generative force for reshaping the nature of knowledge production and the writing of history.This paper examines the diverse practices emerging in the digitization of art history,encompassing database migration, computationally assisted analyses,the mobility of texts and discourses,and the algorithmic rewriting and AI generation that increasingly shape scholarly production.As digital processes generate vast amounts of detail while simultaneously fragmenting discourse through algorithmic operations, they challenge long-standing scholarly hierarchies and established structures of authority. This study employs the concept of “copy” as a metaphorical cue to explore the critical necessity of reconfiguring authenticity and subjectivity in the history of digital art.By redefining who has the right to write,who holds epistemic authority in the digital paradigm,how narratives are constructed and reconstructed,and through what mechanisms knowledge is produced,disseminated,and legitimized,this paper argues that digital art history is gradually distancing itself from historiographical traditions.Ultimately,the entanglement of human and non-human agents ranging from scholars and institutions to algorithms and data infrastructures will fundamentally reconfigure negotiations surrounding art,media,technology,and information.

Keywords: Digital Art History(DAH), digitization, authorship, subjectivity, authenticity, algorithm

Citation: CHEN Lu.The copy writes back:digital art history and the crisis of authorship[J].Advances in Art Science,2025,2(1):139-156.