打破战后挪用艺术中的递归结构: 再媒介化与罗伊·利希滕斯坦的装置

(电影电视系, 艺术学院, 布里斯托大学, 布里斯托 BS8 1QU, 英国)

摘要: 本文指出, 对20世纪下半叶的挪用艺术“以内容与形式双重回应社会现象”的解释框架, 已经面临理论疲软与制度化困境。随着20世纪下半叶的挪用艺术作品、其创作方法论以及围绕在其周围的批评话语被纳入艺术教育、美术馆、艺术市场与视觉资本主义体系, 挪用艺术最初所主张的批判性已逐渐转化为自我循环的、可供消费的新的范例, 和一种罗莎琳德·克劳斯形容的“递归结构”。这一局面对今日的观念艺术创作亦产生着持续的影响。面对这一局面, 本文将延续弗里德里克·詹明信在《元评论》中的思考, 指出: 为何试 图为挪用艺术制定一种“连贯、确定、普遍有效”的结构主义批评话语———即将挪用艺术理解为隐喻、反讽和简单二元对立的呈现———这一企图本身, 正是导致当前批评困境的根源。本文主张应通过对20世纪的下半叶的挪用艺术作品及其批评话语的重新审视, 引入媒介视角, 以细致的、历史的文本分析方法, 重新激活其批判潜力。随后, 本文引入“再媒介化”理论, 回顾和延续了麦克尔·洛贝尔对罗伊·利希滕斯坦作品的文本分析, 辅以对彼得·布莱克等其他艺术家的关注, 提出在20世纪下半叶的挪用艺术中发现一种新的媒介反思方式的可能性。在这一部分中, 文章展示了洛贝尔如何通过对利希滕斯坦作品中关于“单眼视觉”主题和“自然视觉与视觉机械对峙”隐藏叙事的揭示, 研究艺术家的个人经验和其所处的历史媒介环境如何影响他的实践。随后, 本文通过进一步引入维兰·傅拉瑟的“线与面”理论, 提出“尺幅”这一常常被忽略的信息, 如何在观众观看作品的动态中, 与利希滕斯坦标志性的“本迪点” (Ben-Day Dots) 共同构建出一种含有虚拟的“放大镜”结构的、关于“视觉本身”的装置, 并体现出如傅拉瑟所说的, 现代视觉机制中“形象虚构”与“概念虚构”的交互张力。最后, 本文还通过重新审视利希滕斯坦后期作品, 提出这批作品中体现出的“转译”实 验, 不仅与傅拉瑟的展望不谋而合, 还可被视为一种对当下操作图像时代的隐喻。

关键词: 挪用艺术, 消费社会, 元评论, 媒介, 罗伊·利希滕斯坦

引用格式: 张书源. 打破战后挪用艺术中的递归结构: 再媒介化与罗伊·利希滕斯坦的装置[J]. 艺术学研究进展, 2025, 2(2): 285-309

文章类型: 研究性论文

收稿日期: 2025-04-30

接收日期: 2025-06-24

出版日期: 2025-06-28

1 Introduction

The myth becomes a meditation on the mystery of the opposition between Nature and culture:becomes a statement about the aims of culture…and about its ultimate contradiction by the natural itself,which it fails in the long run to organise and to subdue.[66]

—Fredric Jameson,Metacommentary,1971[1]

Understanding appropriation art of the second half of the 20th century within the context of “consumer society”[2],viewing it as a dual response or irony on both content and formal levels[3],has long been considered an effective convention for critical and academic discourse production.At the content level,appropriation artists in the post-war decades generally demonstrate great interest in mechanically reproduced images from commercial activities—from Richard Hamilton’s collages using advertisement images from magazines,to Heidi Cody’s alphabet composed of letters from trademarks,to Andy Warhol’s repeated reproduction,enlargement,and juxtaposition of everyday product images,to Richard Prince’s re-photographing of cigarette advertisements—all exemplifying this trend.At the formal level,appropriation artists parody and exaggerate various behaviours and phenomena in the context of consumer society,thereby constructing a mechanism to deconstruct and ironise consumer society.However,this methodology of responding to consumer society at both content and formal levels,as well as the habitual interpretations and critical perspectives surrounding these works,has long faced a dual loss of criticality.As these classic works entered art galleries,on one hand,because in the practice of appropriation art,artworks no longer function as “medium-specific”(since they are often mixed-media),as Rosalind Krauss states,they are “leveled,reduced to a system of pure equivalency by the homogenising principle of commodification”[4],they have reluctantly become objects of what Krauss calls “appropriate and reprogram” in the capital-dominated art circulation system.On the other hand,the methodologies of appropriation art have gradually become institutionalised and stylised,becoming a “new Academy”[4] and complicit in cultural capitalism.

Meanwhile,the critical discourse around these works has also long faced ineffectiveness:such interpretations often emphasise the signifying relationships between appropriation art and various phenomena in the context of consumer society,simply viewing it as irony,metaphor or parody.Through continuous repetition,these interpretations have become predictable,repeatedly applied in art history/curatorial writing,art trade,and other contexts.A “recursive structure” as Krauss describes—“some of the elements of which will produce the rules that generate the structure itself”[4],has emerged between the methodologies of appropriation art and the discourse of.

Additionally,audiences and scholars rarely delve deeply into this dual response on consumer society and popular culture at the content level,instead taking them for granted.Fredric Jameson already expressed a vigilant attitude toward this structuralist(which Jameson terms “pure formalism” structuralism to distinguish it from his “historical” structuralism)approach decades ago—the seemingly complete and fluid dual critique logic at the levels of content and form[1].What Jameson opposes is not structuralism itself,but rather a structuralism with “key methodological presupposition” [1],a stance that views metaphor and metonymy,rhetorical figures,binary oppositions,and other basic categories of structuralism as ultimate forms of thought.He terms this analytical method an “equation” in which we are at liberty to incorporate whatever content resonates with our interests[1].In the context discussed in this paper,these binary oppositions could be art versus readymade,painting versus printing,handcraft versus mechanical reproduction,creation versus consumption,aura versus loss of aura,freedom versus neoliberalism…Although these oppositions seemingly conform to the “historical” category advocated by Jameson or could be viewed as oppositions emerging from the “locus” of historical[1],in repeated discourse of critique,these oppositions have gradually diminished into the most basic one—that the former is superior while the latter is inferior.Simplifying the relationship between appropriation art and social phenomena into unshakeable rhetorical or metaphorical relationships inevitably leads to a decline in creativity and criticality—more destructive than the fact that appropriation art has become a new paradigm,or the “new Academy”[4],or that the concepts of “consumerism” and “consumer society” are constantly being challenged and destabilized[5],is the very act of presupposing such “equation”[1].What deserves greater vigilance than the rigidity of the automatic critical discourse is the cycle of “recursive structure”[4] between practice and critique itself.The “medium” dilemma proposed by Krauss[4],in which the concept developed alongside critical postmodernism and later generated its own problematic aftermath,does not directly describe appropriation art,but the mechanism she put forward bears considerable similarity to and provides inspiration for the situation mentioned in this paper.In this cycle,appropriation art will not only be unable to generate new critical content but will find it even more difficult to produce critical form.

Therefore,this paper extends Jameson’s perspective to point out that what needs to be reconsidered is not the ontology of appropriation art;nor does this paper intend to overthrow appropriation art’s critique of consumer society,because this criticality is precisely derived from history.What needs to be reconsidered is what Jameson terms the “universal modes of organising and perceiving experience”[1]—this repeated use of metaphor,irony,and the reduction of a series of concepts to binary oppositions with predetermined positions such as good and bad,high and low,which has essentially detached from history.

Under these circumstances,how could this “recursive structure”[4] be broken free from and allow past works of appropriation art to regain their criticality and inspirational value? This paper argues that even under what Krauss describes as the “post/medium condition”[4],it remains meaningful to reexamine another narrative thread in the practices of appropriation art in the post-war decades,namely,the focus on media.Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin’s perspective of “remediation”[6] provides a new possibility for reevaluating appropriation art of the post-war decades:they are no longer simply viewed as readymade art and its numerous variations,but as structures that manifest “hypermediacy”.In this process,we need not only to reexamine the artworks,but also to rediscover the valuable critical discourse surrounding this series of works.This methodology of a media turn does not mean completely focusing perspectives on the form while offering only simplified definitions of content but rather approaching specific historical contexts and artists’ specific experiences,as Jameson contends,restore “original message” and “original experience”[1],as well as reclaiming the inspiration that the works can provide from today’s perspective.Some of the most brilliant and literary critiques of appropriation art are made through meticulous observation and comparison of the content of the works.Michael Lobel discovers a hidden narrative in Lichtenstein’s works:the confrontation between natural vision and mechanical vision[7].Lobel’s focus is also on medium,but this attention at the medium level is not achieved through the appropriation means and mechanical reproduction appearance that seems to override all other content-level motivations,or merely viewing it as a response to vague concepts of pop culture or mechanical reproduction.Instead,it is achieved through detailed textual analysis(composition of the image,text,subtle changes made based on the appropriated images,etc.),as well as through retrospection of the historical environment and the artist’s own experiences.Edward W.Said,in his preface to Mimesis,praises Auerbach’s textual analysis achievements as “elucidating relationships between books and the world they belonged to”[8]—the vital issue is which world Lichtenstein’s work belongs to.The ingenuity of Lobel’s writing lies precisely in placing the context of Lichtenstein’s practices in a world dominated by a second historical time—the world dominated by the historical time of Lichtenstein’s personal experience,his visual perception training,his military experiences during World War II,his post-war work,and so on.This is exactly the narrative hidden by the narrative of a generalised,commercial world in the post-war decades.

Furthermore,this paper introduces Vilém Flusser’s theory of “line and surface”,proposing how the often-overlooked dimension of Lichtenstein’s paintings,“scale”,works together with the iconic Ben-Day Dots to construct an “apparatus”[9].This “apparatus” also embodies the interactive tension between what Flusser describes as “imaginal fiction” and “conceptual fiction”[9] in modern visual mechanisms.The “apparatus” is about “vision itself”,containing a virtual structure of the “magnifying glass”.Adopting Krauss’s description of Jackson Pollock,Lichtenstein’s practice can be viewed as a transformation from “making objects” in an increasingly unified manner to “articulating the vectors that connect objects to subjects”[4].The “medium-specific” of painting is maintained and transformed into a kind of “supporting structure.” Finally,this paper also reexamines Lichtenstein’s late-career works,suggesting how the “translation”[9] experiments embodied in these works can provide theoretical resources for the relationship between “image” and “concept” in contemporary visual culture.

2 The Origins of Appropriation Art

Appropriation refers to “the taking over,into a work of art,of a real object or even an existing work of art”[10] in the context of modern art.Appropriation art dates to Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque’s Cubist constructions and collages made from 1912 onwards,they are also considered to be the inventors of collage art.[11]Although the invention of appropriation art can be traced back several years earlier,it was Marcel Duchamp’s “readymades” that advanced this practice from a method to a paradigm.Duchamp is the first to use the term “readymade”[12],and after World War II,this concept,which had been overlooked for nearly half a century,was rediscovered and utilised by American Pop artists and European “Nouveau réalisme” artists,subsequently gaining enormous success and influence.

Fig.1 Pablo Picasso,Guitar,1912,Paperboard, paper,thread,string,twine,and coated wire, 654×330×190mm,MoMA,640.1973.

Following Braque and Picasso’s sculptures and Duchamp’s readymades,appropriation art developed into various forms in the 20th Century,including collage,re-photography,found-image,etc.,intertwining with movements and schools such as Surrealism,Dadaism,and Pop Art.According toDavid Hopkins,Duchamp’s practice of selecting readymades from around 1913 is led by his dislike for the “craft” traditionally tied to visual art,along with his conviction that concepts,rather than manual technique,should become the primary foundation of artistic creation[12].In his studio,Duchamp installed a bicycle wheel on a stool,two everyday objects readily available anywhere,together to form an object that seemed to have no logic and had never existed before.This event was almost random—as Duchamp,the concept “readymade” did not appear until 1915[6].His later work,Fountain(1916),even omitted the step of assemblage.

Appropriation is an action,or a method.There is no genealogical correspondence between the act of “appropriation” and certain traditional media,as exists between “painting” and “paint,” or “sculpture” and “sculpt.” As a rather broad category,appropriation art always appears with its fragmented partial bodies,such as “readymade”,“collage”,“re-photography”,“found image”,etc.,or is roughly interwoven with the names of art movements like “Dadaism” and “Pop Art”,or is vaguely categorised under overly macro contexts such as “contemporary art” or “conceptual art”,submitting to larger and vaguer commonalities.First,it should be noted that the word “appropriation” is a sign with potentially endless referential meanings,as a symbol can always refer to another symbol.For example,in Collage in Twentieth-Century Art,Literature,and Culture(2014),Rona Cran[11] terms Bob Dylan’s music “appropriated the techniques of collage”.Similarly,there are other meaningful rhetorical gestures like using “appropriation art” as a symbol for Bob Dylan’s music.However,if we follow this expansive approach,the object of discussion in this paper would be endless.Therefore,the scope of appropriation art discussed in this paper is limited to artworks that adopt the few media aforementioned.There is another concept that needs to be distinguished.In Remediation:Understanding New Media(2000),Bolter and Grusin[6] mention an act of “repurposing”:“to take a ‘property’ from one medium and reuse it in another”.They cite,as examples,film adaptations of Jane Austen novels from the 1990s.These films neither reference the original novels nor acknowledge themselves as adaptations,instead aiming to offer audiences familiar with novels a sense of continuity and immediacy.Bolter and Grusin also trace this practice to a long-standing pedigree—paintings depicting scenes from the Bible or other literary works[6].In these cases,what is borrowed is the content,meanwhile,the medium is not appropriated[6].These paintings and films should not be seen as,and have never been considered as,“appropriation art”.

3 Dual Response

Although “appropriation art” is a broad category,two vague narratives can still be unfolded:The first responds to commercial culture(or consumer society,consumerism,and some other different terms①),which is doubly constructed at the content and formal levels,becoming an enduring theme of appropriation art in the 20th century.For instance,Pop art,as a representative form of appropriation art,emerged from consumer society and simultaneously responded to it through rhetorical strategies such as exaggeration,metaphor,and irony.It is also a quite popular way of interpretation and critical discourse about appropriation art among the public and academia.Theories such as Jean Baudrillard’s semiotic critique of consumer society[14],provide a foundation for this mode of understanding.At the content level,this response is obvious:After World War II,the vast amount of visual material and commodities brought by the flourishing commercial culture naturally provided appropriation artists,including Pop artists,re-photography artists,and artists creating with found images and readymades,with an abundance of materials.At the formal level,through simulation,exaggeration,and distortion of the essence of consumer society and a series of phenomena under its context,appropriation art brings the ambition of

① Different scholars have different rhetoric regarding the impact of consumer culture on the 20th century.For example,Zygmunt Bauman[2] advocates that “ours is a consumer society”.The definition is relatived to the previous “producer society”,a definition mainly based on the way in which the society shaped up its members was dictated by the need to play this role and the norm that society held up to its members was the ability and the willingness to play it.Frank Trentmann[5],in the essay Beyond Consumerism:New Historical Perspectives on Consumption(2004),on the other hand,relatively mildly acknowledges the “centrality of consumption to modern capitalism and contemporary culture”.

capitalist commodity economy and its alienating effect for humans into stark relief.

From Duchamp and collagists of the Dada period to post-war Pop artists,their creative processes all implicitly contain similar gestures to various behaviours in the context of the 20th-century consumer society,becoming a rhetoric of exaggeration and metaphor.From the perspective of an observer contemplating the process of creating MoMA’s displayed Bicycle Wheel,one of the earliest appropriation artworks,these steps the artist takes in finishing the work can almost correspond one-to-one with people’s actions and psychology in the consumption process:consumers’ act of browsing,selecting,and purchasing goods is like Duchamp’s process of searching for and deciding to use a bicycle wheel and a stool from readymades;the consumer’s act of recombining purchased goods(usually clothing,jewelry,furniture,etc.)is like the artist’s behaviour of combining the bicycle wheel and stool;finally,consumers view certain goods or combinations of goods as materials for constructing their own identity—as Peter N.Stearns maintains,“become enmeshed in the process of acquisition shopping - and take some of their identity from a procession of new items that they buy and exhibit”[15],while the artist views these readymades or combinations of readymades as their own work,which conveys their own concepts.Readymade presents an irony of consumer behaviours through a parody of consumer behaviour(although according to Duchamp,this work was formed unintentionally[6]),plus the exaggerated rhetoric formed by the shock these works initially caused when appearing in art galleries.The signifier provided by Bauman in his analysis of consumer behaviours seems to be the best explanation for this connection:Bauman[2] precisely uses the word “appropriate”,declaring that “being a consumer also means—normally means—appropriating most of the things destined to be consumed”.

Another main form of appropriation art,collage①,also demonstrates the reasonableness of this dual response:in Collage Culture(2013),David Banash[3] makes a brilliant comment on this metaphor—collage is the key to understanding the 20th century as it reflects both the Fordism mode of production that shaped the first half of the century and the consumerist spirit that dominated the post-war era.Artists using collage techniques abandoned the long-held beliefs of craftsmanship,control,and intention among artists,incorporating appropriation and randomness into artistic creation.

① In Collins Dictionary[16],the word “collage” is explained as:“1.An art form in which various materials or objects are glued onto a surface to make a picture.2.A picture made in this way.3.A work,such as a piece of music,created by combining unrelated styles.” In the online Cambridge Learner’s Dictionary[17],“collage” means “a picture made by sticking small pieces of paper or other materials onto a surface,or the process of making pictures like this.” The contrast between Collins Dictionary’s expansive third definition and the definition in Cambridge Learner’s Dictionary perfectly illustrates the semantic expansion the term has undergone.Like the case of the word “appropriation” just mentioned,in order to avoid the almost infinitely expanding meaning of “collage” when describing modern art,life,and social phenomena,and the infinite proliferation of academic discourse,some brilliant expansion of the category of “collage art” needs to be abandoned in this paper.Cran’s example again,Cran[11] mentions works by authors using other artistic media who “mimic visual collage,” including Joseph Cornell’s assemblage,William Burroughs’ novels,Frank O’Hara’s poetry,and Bob Dylan’s music(Cran[11] quotes Dylan saying his music is a “collage of experience”).Cran suggests collage’s significance stems from both its practical applications and conceptual flexibility,and the techniques of collage are “appropriated” by the four artists.Nevertheless,none of them is claimed to be a collagist[11].This paper must temporarily exclude these artists from the category of “collage art.” When viewing “collage” as an aspect of appropriation art,its realm is limited to what Picasso and Braque invented,as a specific artistic technique rather than an all-encompassing metaphor for cultural production.

The invention of collage solves the problem for some artists who lack painting skills,as the materials are often photographs or other printings,usually not requiring a lot of craft.After searching for and selecting materials,artists cut out the needed parts from existing newspapers,magazines,or flyers,organising,arranging,and glueing them onto a new blank base board.What is similar on a metaphorical level is that in consumer society,production departments with a clear division of labour and the efficiency of assembly lines bring an almost unlimited variety of goods to choose from;the era of engaging in manual labour and self-sufficiency has gone forever.Consumers no longer need to master any production technology to have almost unlimited freedom of choice.Through consumption,they can be “collagists” of life,or in Bauman’s words,artists of “appropriating”[2].

As Banash advocates,what appropriation art responds to is not only the surface characteristics of consumerism,but also includes its underlying dynamic mechanism—Fordism[3].Antonio Gramsci defines the most widespread use of this term today:Gramsci believes that the assembly line brought about enormous transformations to society,culture,and the psychology of the working class,to the extent that its influence extended beyond the factory,becoming a hegemony affecting the entire society.One characteristic of Fordism is standardisation[18].Fordism can be seen as an allegory for today’s highly fragmented yet homogenised information,conceptions,and lives—the countless cars produced on the assembly line from interchangeable parts and the same in their internal structures serve as metaphors for the masses shaped by standardised opinions,information,and mass-produced commodities.Appropriation art,including readymade,collage,and other media,all directly use standardised,mass-produced or printed objects from Ford-style assembly lines,such as Duchamp’s bicycle wheel,Hannah Höch and John Heartfield’s newspapers,magazines,political flyers,etc.,and reveal the psychology and behaviour of consumers in consumer society in a parodic way.

When appropriation art is understood as a dual logic responding to consumer society at the “content-form” level,Hamilton’s collage Just What is it that Makes Today’s Homes so Different,so Appealing?(1956)can be seen as its typical representative.The work demonstrates how a couple of “liberal person” in consumer society arranges their domestic scene.According to Alastair Sooke,the title of this work is found by Hamilton in the captions of illustrations from a 1955 Ladies’ Home Journal[19].During this period,Hamilton uses material from illustrated magazines and other American ephemera,mostly brought back from the United States by his collaborating artist,the collagist John McHale.Through selective choice and display of these commercial images intended for marketing purposes,Hamilton creates a parody of American advertising in the post-war consumer society of the 1950s,criticising consumerism’s extravagance,impracticality,and inflammatory nature,as well as modern people who are deeply trapped in it and unable to extricate themselves.The living room of this middle-class couple is filled with trendy appliances,furniture,and carefully arranged decorations.They are surrounded in the middle and proudly displaying their enviable possessions and declaring ownership of everything around them.However,this scene that is full of carefully woven ideals reveals astonishing absurdity and strangeness—surrounded by the ocean of luxury goods,humans appear so insignificant.The owners are alienated into puppets of commodities,reduced to plastic models that set off the atmosphere when displaying goods.This symbolisation of commodities also spontaneously forms what Baudrillard describes as an “unconscious mechanism of integration and regulation”[14].The system,contrary to equality,operates by positioning individuals within a framework of “differences”,embedding them in a “code of signs”[14].Hamilton’s work is precisely to present this “unconscious” in an absurd posture.Although I will explain next why this critique loses its critical edge,these works at least once constituted a logically complete critique and contributed brilliant metaphors and connections.

4 “Appropriated and Reprogrammed”Appropriation Art,and the Absence of Metacommentary

In this process,a problematic situation gradually emerge:both the appropriation art and the critical discourse around these works have long faced ineffectiveness:Even ignoring the unreliability of theories such as “consumerism” and “consumer society”[67],firstly,readymade,or appropriation art,lose their criticality after entering the circulation domain of capitalism because,as Krauss,capitalism itself is the ultimate master of “détournement”,which can “appropriate and reprogram” everything to further its own purposes[4].Artists can name commodities as “readymade”,while artworks can also be transformed into variable tradable forms.Those works criticising consumer society and mass culture are those of the first to be targeted:Typing “Andy Warhol” in Google’s image search bar,one will find in the “Ads” column before the search results,there are various pictures features framed Andy Warhol decorative prints in home,dining,and office settings.Another example is that a few years after the main creators of the videogame Disco Elysium(2019)tactfully announced they had been forced to leave the studio,videogame merchandise is still being sold on the atelier.zaumstudio.com website.Perhaps one of the most amusing of these goods is a “appropriated” prop:a yellow plastic bag marked with “Frittte”,once the protagonist finds this bag,he can begin earning a meager income through scavenging,is developed into a collector’s item priced at over 100 euros[20].This image appearing in the video game has been “appropriated” or “reprogrammed” by capitalism.Advertising photos are also featured for this product:a homeless-style hooded model standing on the street,with film noir-style chiaroscuro lighting casting his shadow on the ground.With the blessing of this tattered plastic bag,our protagonist lives a life almost as far from “consumer society” and “capitalism” as we can imagine—that of a scavenger.The protagonist’s attitude of resistance against capitalism is delightfully witty(the videogame itself is also permeated with a similar attitude),yet,this garbage bag,as a symbol of such resistance,has still,due to its popularity,been developed into a consumer good,marketed by a model in a hood posing as a vagrant,“repurposing” the experience of street hardship.Of course,the examples above are merely two insignificant instances among countless similar events.

Secondly,this mechanism of viewing the appropriation art as a “dual response” is rarely truly contemplated.For example,audiences have become accustomed to thinking that Richard Prince’s re-photographed work Untitled(Cowboy)(1989)responds to advertising’s false promises and the absurdity of its meaning-making,simultaneously operating on both content and formal levels.Let’s try to analyse this work from this perspective:at the content level,this image of Western myth that appears completely natural at first glance,however,the ideal lighting angles,or the perfectly timed actions and positions of the man and horses,the dust kicked up by hooves and the perfect shape of the horse’s tail,all suggesting that this image is merely a fairy tale scene meticulously crafted by advertisers,photography teams,and models,to evoke cigarette customers’ daydreams about Western life.This is not the romantic West,but an advertising set with tired photographers and models;this scenario is not reality(no need to ascend to a metaphysics of the medium),but one frame selected from hundreds of negatives.At the formal level,the ironic critique of the absurdity of advertising’s desire-generating process is delivered through an almost absurd parody of appropriation gestures:taking a photograph of a billboard with a portable camera is as simple as buying a pack of Marlboro cigarettes on the street corner—however,does rephotographing a commercial advertisement production with a portable camera signify the author’s identity as an artist—just as buying a pack of Marlboro cigarettes supposedly allows smokers to be as free,wild,and masculine as a Western cowboy?

Similar to modernist artists’ strategy of liberating painting and sculpture from representation,giving them a subjective in the real world by abandoning content,appropriation art also begins with Duchamp’s practice of essentially abandoning content—Duchamp’s readymade arts are purely formal(a bicycle wheel could just as well be a urinal).However,the inheritors of appropriation art,in the post-war Pop Art movement,displayed a fixation on the themes and content of commercial culture.This transformation logic runs precisely counter to the trend of painting moving from representation to the abstract.If the urinal itself already constituted the complete logic of the ultimate critique of consumer society,how could Pop artists’ appropriation of commercial images be understood? In other words,what if Prince photographed something other than Marlboro advertisements? Does this strategy cunningly avoid the risk of interpretive difficulties arising from the absence of audiences’ understanding at the formal level of his work,or does this straightforward appropriation method—simply photographing outdoor cigarette billboards with a camera,taking them to an ordinary street photo lab,and obtaining a large-format colour print—contains some more sophisticated motivation?

In Metacommentary,Jameson[1],through his evaluation of Gogol’s work,proposes a tendency of “an imperceptible slippage from form into content”.His analysis reminds us that if a work,in form and content,exhibits some kind of unity,it should not be viewed,at least not simply,as a natural phenomenon.As Jameson terms,“it is…a misconception to imagine that in Gogol form is adequate to content…it is because Gogol wishes to work in a particular kind of form…he casts about for raw materials appropriate to it.” Drawing on Viktor Shklovsky’s view(“Don Quixote is not really a character…but rather an organisational device which permits Cervantes to write his book”),Jameson raises the question of whether a deeper connection exists between these Western “myth” figures and their technical role in organising and unifying vast amounts of diverse material.From this dimension,Jameson’s theory fundamentally challenges this type of critical discourse,a seemingly perfect form-content duality of critique,on appropriation art.

Jameson attempts to trace the historical mechanisms of emergence and the appeal of the “pure formalist” structuralism critique that he opposed.Russian Formalism brings a significant transformation in the relationship between the literary object and its “meaning”,that is,the separation between form and content.Then the Formalists “reversed this model”—considered technique’s sole purpose as production of art—“now the meanings of a work,the effect it produces,the world view it embodies…become themselves technique:raw materials which are there in order to permit this particular work to come into being.” Therefore,in this premise,with this reversal of importance between form and content,the work must now be viewed from the producer’s perspective rather than the consumer’s.The Formalists completed a critical revolution.The appeal of this structuralist research method is then demonstrated through the evolution from plot novels to plotless novels.In the novel with a plot,“events have their own inner meaning along with their own development”.However,when facing plotless novels,a situation emerges—the sentences could not be explained but the “distinctive mental operations” can—at this point,a tendency appears,in Jameson’s phrases,“throws everything in an inextricable tangle one floor higher,and turns the very problem itself(the obscurity of this sentence)into its own solution(the varieties of Obscurity)”.

The main category of structuralism method is the concept of “binary opposition”,which Jameson critiques as “…replace the substance(or the substantive)with relations and purely relational perceptions…the noun,the object,even the individual ego itself,become nothing but a locus of cross-references:not things,but differential perceptions…a sense of the identity of a given element which derives solely from our awareness of its difference from other elements,and ultimately from an implicit comparison of it with its own opposite”.Subsequently,Jameson presents a thorough questioning of this position:“the interpretation by binary opposition depends therefore on a process of increasing abstraction…a concept sufficiently general to allow two relatively heterogeneous and contingent phenomena to be subsumed beneath it as a positive to a negative”.This compels us to consider the next question beyond the reliability of this “dual response”:when a rhetoric-based referential relationship is repeatedly emphasised and utilised for its convenience,have we already fallen into the trap of a presupposed “binary opposition”?

Nevertheless,what Jameson[1] opposes is not structuralism but a “pure formalist” structuralism,an “equation”.This “equation”,applicable to analyses of all situations,“the variables of which we are free to fill in with whatever type of content happens to appeal to us…as it were,involuntary content of Structuralism itself as a statement about language”.Jameson advocates for transforming this structuralism with predetermined positions—fixed,ultimate,and universal structuralism—into a “historical” one.Although this critique at the content-form level does indeed consider history,and artists and critics have,as Jameson discusses,discovered a binary opposition from history—history gave birth to both modern art and assembly lines and readymade culture—however,as mentioned earlier,through extensive repetition,this opposition returns to its most primitive form:the artist’s actions are continuously viewed as a kind of metaphor or symbol,and the meaning this symbol points to is almost unchanging.Arts always looks down upon readymades from a position of superiority,displaying an emphasis on a rhetoric of “irony” or “metaphor”,and this positional relationship is also almost unchanging.

It’s time to return to the question of Prince:is it still reasonable to view the dramatic conflict in this perspective of presupposed binary oppositions,seeing the tension between the fact this work produced under this almost absurdly simple creative methodology and the event of becoming the world’s most expensive photograph,or the tension between the work’s intention to ironise commercial culture and its enormous commercial value,as the only essence of this work? The answer must be negative because,under the seizure of cultural capitalism and the institutionalisation of criticism of appropriation art,a “recursive structure” has formed:under this criticism with predetermined positions,both works and understanding of works are mass-produced.This situation already conforms to what Krauss considers “the most pessimistic prediction makes by Marcel Broodthaers”[4]:“…any theory,even if it is issued as a critique of the culture industry,will end up only as a form of promotion for that very industry”,the discourse and the practice form the ultimate complicity,“the ultimate absorption of ‘institutional critique’ by exactly the institutions of global marketing on which such ‘critique’ depends for its success and its support”.

Therefore,on one hand,appropriation art,caught in the predicament of being appropriated by cultural capitalism,urgently needs to restore new criticality;on the other hand,only by allowing criticism of appropriation art to break free from the cycle of binaries such as metaphor,rhetoric,andsimple binary oppositions can this “recursive structure” be broken.Thus,this paper argues that even under what Krauss calls the “post/medium condition”,at this moment,we should at least direct more attention toward the second driving force embodied in appropriation art practices in the post-war decades beyond responding to consumer society:reflection on media ontology.

Besides introducing a media perspective and reexamining appropriation works,reassessing the “content” of appropriation art from this period is equally essential.Although this paper has consistently emphasised appropriation art’s dual response to social phenomena at both content and form levels,to a large extent,value judgments about the content of appropriation art still remain at a simple structure of viewing appropriated materials as symbols pointing to phenomenon,and considering them as satires of these phenomenon(for example,viewing the advertisements in Prince’s re-photography as satire on advertisements,viewing the West scenario in Prince’s work as an irony of an American myth,or viewing letters from logos of American corporations logos in Cody’s works as satire on American corporation culture,etc.).This analytical approach only nominally pays attention to History;in fact,this History is only loosely and obscurely summarised as the history of the “consumer society” or other similarly unreliable concepts.

Therefore,this paper advocates a return to detailed textual analysis strategies in order to uncover the“true history” embedded in the content of the works—a history that,at the very least,should be rooted in the artist’s personal experience and specific historical context.If this history is continually reduced to a vague generality(such as “consumer society”),then any effort to identify the true generative mechanisms behind a work,a style,or a methodology is liable to fall back into the same “recursive structure”.

5 Media Turn and New Content Concern

A frequently overlooked fact is that,whether appropriating readymades,parts of prints,or images and others’ artworks,appropriation art not only signifies a change in the object’s “identity”(for example,bicycle wheel to art),but always involves a transformation of medium.This transformation often manifests as the appropriation of “experience of media”,the act of a medium absorbing characteristics of the other medium[6].However,first,not all artists highlight this “play of media” in their work;second,different audiences inevitably perceive this mechanism to varying degrees.This necessarily involves some speculation and personal experience—when I first saw Warhol’s work as a teenager,my impression was merely of colourful Marilyn Monroe images.The reason is that the media itself is not obvious and can even be said to excel at hiding itself.Scholars,such as Marshall McLuhan[21],Friedrich Kittler[22],or Joseph Vogl and Brian Hanrahan[23],have noted this paradox of media,namely that while media has such a profound influence on our senses and perceptions,it tends to conceal itself,or as Vogl and Hanrahan[23] advocates,“a tendency to erase themselves and their constitutive sensory function”,making the media themselves “imperceptible” and “anesthetic”.

Through referencing McLuhan,Bolter and Grusin[6] illustrate a different mode from the “repurposing” model mentioned at the beginning of the paper that only borrows content,and there is “no conscious interplay between media”.In the new mode,“the ‘content’ of any medium is always another medium”.Bolter and Grusin subsequently argue that what McLuhan contemplates is not just “repurposing” but a more complex mode of “borrowing”,a “representation of one medium in another”.In this case,the “experience” of one medium is absorbed by another,the language of the medium itself is appropriated.This process is the mode of “remediation”.

The paradox that Bolter and Grusin repeatedly mention is:the act of “remediation” is always accompanied by a concealment of this “remediation”.This reveals to some extent why,even though appropriation art almost always involves this “remediation” process,this process is not always visibly apparent.A fictional device from the film Strange Days(1996),“the wire”,is cited as a metaphor of the common demands on media:this device has recording and playback functions—in recording mode,it can capture the sense perceptions directly from the brain of the wearer;in playback mode,it can transmit what was previously recorded through the brain straightly to another person.Without any forms of mediation,this device transmits from one person’s consciousness directly to the other.As Bolter and Grusin term,this device demonstrates a “double logic” of “remediation”,a “contradictory imperatives for immediacy and hypermediacy”:“our culture wants both to multiply its media and to erase all traces of mediation:ideally,it wants to erase its media in the very act of multiplying them”.Numerous examples to illustrate this “double logic”,including the perspectives in television Live,location shooting or period costumes for giving viewers the “real” feeling,could be provided.In this process,both old and new media are utilising these two logics of immediacy and hypermediacy to reshape themselves and each other to satisfy the pursuit of immediacy.According to Bolter and Grusin,even the most hypermediated products pursue this immediacy(they cite CNN news,flight simulation videogames,and web pages as examples),and the immediacy of some products is achieved by being hypermediated.This pursuit of immediacy could be traced back throughout the Western visual representation history of recent centuries,for instance,Edward Weston’s photography and live broadcasts of the Olympics,both “attempts to achieve immediacy by ignoring or denying the presence of the medium and the act of mediation”.This attempt can be traced back at least to the invention of linear perspective during the Renaissance.Bolter and Grusin also take note of appropriation art,with the object of their analysis being Hamilton’s work mentioned above.Besides viewing collage or photomontage as a rhetoric for the “hypermediacy” appearance widely present today,they also use collage as an example of how old media present strong discontinuity in new media[6].

Re-examining appropriation art in the post-war decades through the perspective and methodology of these three concepts,“remediation”,“immediacy” and “hypermediacy”,can be one of the effective strategies.Because the concept “remediation” reveals the operational mechanism at the media level of appropriation art;“immediacy” explains why this operational mechanism is often overlooked,and “hypermediacy” is an explanation at the media level of the completed state of appropriated art.Some of the most perceptive artists,such as Harry Callahan,Peter Blake,and Roy Lichtenstein,built upon the dominant narrative of responding consumer society and mass culture,and—either explicitly or implicitly—embodies a contemplation towards medium in their works.

Before analysing Peter Blake,I would like to begin with a work by Harry Callahan:Collages(c.1956).In this work,hundreds of fragments of photographs are assembled into a single image that resembles either a disco ball composed of beautiful faces or a twentieth-century mosaic—glamorous,mysterious,dizzying.On an immediately perceptible level,the work conveys a deep anxiety about fragmentation and homogenisation:the faces appear frustratingly sameness.This work operates as a typology that stands in stark contrast to the monumental documentation of August Sander’s portraits.Yet one detail demands attention:the medium of this work is contact print,a gelatin silver print,the medium closely associated with photography,not collage.Even the title itself carries a double meaning — “collages” refers to a medium,but not to the medium of the work.It is a gelatin silver print of a collage,and a gelatin silver print about collage.So,this work is not merely a print with “immediacy” about homogenisation and Fordism,but also about the medium,or “remediation” and “hypermediacy”.

Fig.2 Peter Blake,On the Balcony,1955,oil paint on canvas,support:1213×908mm,frame: 1324×1017×50mm,Tate,T00566

Fig.3 Harry Callahan,Collages,c.1956,Gelatin silver print,195×243mm,MoMA,505.1999

If Collages is a collage “remediated” photograph,then On the Balcony(1955)is a collage “remediated” oil painting.In the process of “remediation”,the old medium is absorbed by the new medium.There are discontinuities between the old and new media.And the new medium(oil painting)still depends on the old medium(collage)to make sure that the old medium cannot be totally erased[6].Blake constructs a middle-class life scene in consumer society in this painting.Flat images appearing in the painting include Life magazine covers,black and white photographs,etc.But the surrealism figures’ images,and the linear-perspective-bearing table and bench seem to create an awkward situation:is there a possibility that Blake is using a surrealist style to depict a real,unusual scene,where the paintings and prints that appear to float on the surface of On the Balcony all actually exist in this scene,just perpendicular to the painter’s perspective? If so,this painting becomes a modern edition of The Archduke Leopold William in his Picture Gallery in Brussels(1647-1651),except that the oil paintings in it have been replaced by black and white photographs and magazine covers,and they are placed in a somewhat strange manner.However,one thing is certain:this painting does indeed contain “experiences of media”[6] from collage,such as overlapping and the appearance of mechanically reproduced images:they are placed in an ambiguous zone between linear perspective,surrealism,flatness,and materiality,making them look more like they are pasted onto the canvas rather than being in the picture.In other words,this is a practice of “hypermediacy”,like Dutch painters incorporating maps,letters,paintings within paintings and so on into their works,or filmmakers combine real action footage with computer-generated images,two-dimensional and three-dimensional computer-generated graphics,television news producers integrate text on screen mentioned by Bolter and Grusin[6]. However,the artist’s task is not like that of the digitised image gallery,making the audience feel the same way they did with this new medium as they did with the old one[6],but rather to reveal the state of “hypermediacy” in this “remediation” process.

6 Rearticulating Lichtenstein

Through observation of another appropriation artist,Lichtenstein’s entire career,it becomes easier to discover this mechanism of “remediation” and “hypermediacy”.His early works appropriating images from printed materials such as comics and advertisements are viewed as an important component of the Pop art movement concerned with materiality,commodities,and mass culture,gaining considerable public recognition.Taking Whaam!(1963)as an example,according to the exhibit text provided by Tate Modern[24],this piece is appropriated from a single panel in the DC comic in 1962,then the moment of the fighter destroying an enemy aircraft demonstrated in the comic is enlarged and divided into a diptych form,supplemented by the pilot’s dialogue bubble and the visual impact of the onomatopoeic word “WHAAM!”.The caption for this work can be seen as a common interpretation:“through Lichtenstein’s quasi-absurdist treatment…this deconstruction of military heroism could be read as a statement on the folly of war”[24].This paper is not intended to deny the thematic significance of Lichtenstein’s early works or the visual shock they brought to viewers,but rather,contends that the theorisation of Lichtenstein’s works at the medium level,especially the interpretation of his later works,remains somewhat lacking even to this day.Through close examination of all of Lichtenstein’s works from 1940 to 1997,as collected on lichtensteincatalogue.org,one can trace a clear shift:the ironic tone rooted in popular culture and commercial imagery is gradually replaced by deeper reflections on artistic subjectivity and the nature of the medium[25].Lichtenstein’s practice took a turning point with the mid-1960s Brushstroke and Landscape series;in these two series,Lichtenstein almost abandons the appropriation of content,using only iconic symbols representing mechanical reproduction’s visual style—Ben-Day Dots,flat colour,lines,and high-contrast saturated colour—to compose images that appropriate the “experience of medium”[6] of printed materials.

Under traditional commercial models,there indeed exists a process of “remediation”:an original draft created by an artist or designer is always then reproduced into any number of materials(advertisements,posters,paper comics,etc.)with the help of printing technology.It’s not hard to see that Lichtenstein is simulating a process almost in reverse of how his appropriated objects were produced.When creating his early famous works such as Whaam!,Lichtenstein uses images from comics and outdoor billboards as appropriation materials,first cropping and modifying them,then projecting them onto canvas,outlining the contours according to the projection,finally colouring them.This creative approach did not begin in the 1960s but was a task during Lichtenstein’s military service in World War II[7]:when his superior discovered he was an artist,Lichtenstein was asked to enlarge and mount comics from the Stars and Stripes newspaper.When Lichtenstein began creating in this manner again around 1961,he deliberately started adding the appearance of mechanical reproduction to his works,most representatively by manually adding Ben-Day Dots that would only appear in prints.

Fig.4 “Physiognotrace”[26]

Lichtenstein creates both a precise and rough appearance for these works:the precision lies in viewers naturally seeing these oil paintings several meters long as proportionally enlarged single or multiple comic panels rather than something else,thanks to Lichtenstein’s carefully designed method of projecting:Lichtenstein uses a projector to enlarge the modified comics,then traces the shadows with the pencil.This is almost a reenactment of the prehistory of photography:before photography was invented,a device called “Physiognotrace[26]” that could mechanically trace a proportionally reduced silhouette of a person’s profile was once very popular.This device reflects humanity’s desire for mechanical reproduction methods,and the later improved devices reduced human factors to a minimum(but not eliminated).With the emergence of photography as a genuine method of mechanical reproduction,this device was relegated to obsolescence and forgotten.Nevertheless,the roughness lies in the fact that these works were undoubtedly made by human effort:the Ben-Day Dots,seemingly models of mechanical reproduction,are painted with brushes,bearing obvious handcrafted traces[27];though the images are proportionally enlarged with a projector,they are copied onto canvas by the painter with pencil,rather than using light-sensitive materials like gelatin silver emulsion for mechanical reproduction;these comics at first glance seem almost like enlargements of the originals,but careful observation reveals that Lichtenstein often made subtle changes to serve his themes.

Therefore,his work is not imitating printing,but in a reversal of the process of “remediation[6]” in the common commercial workflow,reveals the difference between painting and printing,the inimitability of printing.The dots are undoubtedly very distinct from true Bendays dots,in terms of the mechanism of generation(mechanical versus manual),in their arrangement and size.Lichtenstein uses a backwards action and device to recreate the state before the emergence of image mechanical reproduction means,photography.This device,coincidentally or awkwardly positioned between painting and photography both historically and at the medium level,is itself a metaphor for Lichtenstein’s work:a rough precision(or precise roughness),a handcraft with mechanical reproduction qualities(or mechanical reproduction with handcraft qualities).However,it doesn’t diminish the self-reflexivity of the relation of human craft and mechanical reproduction in Lichtenstein’s works,but rather increases it.

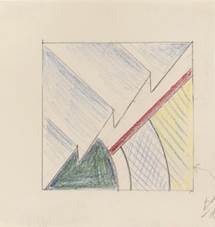

Fig.5 Roy Lichtenstein,Blue and Green Modern Painting(Study),1967,Acrylic,oil,Coloured pencil, graphite pencil on paper,Sheet:121×117mm,Image: 76 × 78mm,Private collection

Fig.6 Roy Lichtenstein,Blue and Green Modern Painting,1967,Acrylic,oil,graphite pencil on canvas, 610 × 610 mm,Private collection

Lichtenstein almost resolutely maintains dots,flat colours and unyielding lines as key components of his copying process[28].Taking his most iconic Ben-Day Dots as an example,surveying his 5292 works from 1940 to 1997 on www.lichtensteincatalogue.org[25],it could be observed that in Lichtenstein’s early use of Ben-Day Dots(beginning around 1961),these dots are often uniform in size,evenly and flatly distributed[25].After a series of experiments,around 1967,Lichtenstein seemed to discover a way to organise these “morpheme” of printing,which representing the smallest indivisible parts of prints,into “vocabulary”:using Ben-Day Dots of varying sizes,but still evenly spaced,to express light and shadow variations in certain areas of the image.Through comparison of the work and draft,this correspondence becomes clearer.This treatment also frequently appears in the artist’s later mirror series.Ultimately,a mirror and Ben-Day Dots of varying sizes together constitute the most important elements in the artist’s famous Self-Portrait (1978):in this self-portrait,the painter’s head is replaced by a mirror,and the image in the mirror consists of Ben-Day Dots of different sizes.The symbolism of the mirror means that Lichtenstein has completely equated himself with an “image-duplicator”[7],simultaneously,another aspect of his identity as an artist is linked to these Ben-Day Dots of varying sizes.

7 Textual Analyses Back to the“Historical” Realm

The idea advocated by Jameson in Metacommentary[1],the history itself,the historical situation of the work and the commentator,is what “genuine interpretation” direct attention back to—not only coincides with Said’s description of Auerbach,but also proposes a new vision—Jameson maintains that the interpretation should arose from cultural necessity and from that society’s dedicate efforts to incorporate significant works from different historical periods and regions—reviewing past works from today’s perspective and discovering new criticality.Lobel discovers that,besides binaries including commerce/mass media-emotion/experience,painting-printing,handicraft-mechanical reproduction,etc.Lichtenstein’s works contain another binary opposition,an undercurrent hidden beneath these widely discussed themes.In Lobel’s words[7],“the relation between embodied vision and machines”.Lobel traces this theme back to the influence of Hoyt Sherman:Lichtenstein,while pursuing his undergraduate degree,received his first intensive and systematic art training under Sherman’s guidance.After World War II,from 1946-1949,Lichtenstein returned to teach at Sherman’s “flash lab.” In these two experiences,Lichtenstein participated in Sherman’s grand visual experiments.[7] Sherman’s experiments were designed based on a concept:the different components of the human perceptual process,such as binocular vision or a priori knowledge of various objects in the world,interfering with the unmediated perception of the visual field[7].According to Lobel[7],Sherman established a painting training program using a device called the “tachistoscope”,requiring students to observe flash images lasting from a fraction of a second to a few tenths of a second in a completely dark environment,then drawing the patterns they barely glimpsed based on the afterimage on their retinas.As Lichtenstein’s description,the purpose of the program is to increase visual acuity and help students suppress prior knowledge that encourages them to categorise perceived objects into things,items,or human bodies.

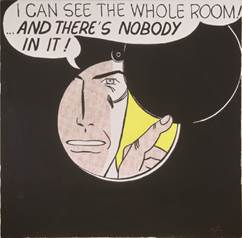

Fig.7 Roy Lichtenstein,I Can See the Whole Room!…And There’s Nobody in It!, 1961,Oil,graphite pencil on canvas,1224×1222mm, Private collection

Lobel[7] astutely points out the potential contradictions and conflicts behind this program:it has humanistic pursuits,evident from its aim to improve students’ aesthetic abilities,but at the same time,this pursuit is achieved through enhancing their capabilities by mechanical means.Under such demands,the subject is required to become a machine,which is capable of perfectly recording various visual forms in the world without being disturbed by subjectivity—such a machine does indeed exist in the world,and that is the camera.Lobel[7] believes that a recurring theme in Lichtenstein’s works,which Lobel summarises as “monocularity”,is related to his various experiences mentioned above.“Monocularity” implies an unusual relationship between human and machine—first,monocular viewing might suggest a state of being forced to observe with one eye due to approaching an optical instrument;second,the single eye implies that as the human body approaches the optical instrument,its subjectivity is threatened.

Lobel notes Lichtenstein’s 1961 workI Can See the Whole Room!…And There’s Nobody In It!,which presents a scene of a man peering into a completely dark room through a small hole.Above this hole,there is a circular plate that can be rotated up and down.Lobel points out that Lichtenstein may give this appropriated image with a film noir look an entirely different meaning:this is not a door with a peephole,but a 19th-century camera.In Sherman’s flash laboratory,students’ subjectivity was effectively erased;they were required to become instruments that could only record visual stimuli,providing a new perspective for understanding this Lichtenstein’s work:this person is not saying there is “nobody” in the dark room,but rather that there is “no body” inside.[7]

Lobel then lists a series of works embodying “monocularity.” By comparing these works with their original appropriated images and discovering subtle modifications—an approach often considered effective for analysing Lichtenstein’s themes and intentions—Lobel[7] finds that these works all imply a conflicting narrative:human eyes viewing through some kind of optical device,such as submarine periscopes,rifle scopes,fighter jet computing reflector sight,which are all used to enhance or correct human vision.The human in these works often face these optical machines in a confrontational posture.For example,in Torpedo…Los!(1963),the right eye of the submarine captain,which is tightly closed while looking through the periscope in the original comic,is changed to look wide open and placed in the centre of the composition.Another work with a similar theme,Jet Pilot(1962),depicts a scene of a pilot intently gazing with both eyes at one such machine,the fighter jet’s computing reflector sight.Compared to his appropriated prototype,Lichtenstein makes subtle modifications in his work:the narrative focus changed from the broken tube on the pilot’s oxygen mask in the original comic,guided by a row of bullet holes in the fighter windshield,to the computing reflector sight in front of the pilot.During World War II,Sherman’s training program played a role in the training of pilots,and it was during this period that Lichtenstein interrupted his undergraduate studies to join the military.Although Lichtenstein never received pilot training,according to his recollections,similar targeting devices were also present on the anti-aircraft guns he trained with[7].Lobel believes that this experience allowed Lichtenstein to rethink the relationship between the body,vision and the machine.Such reflections were condensed into a theme,“monocularity”.According to Lobel,in Lichtenstein’s work,early monocular visual representations give way in later works to the aggressive binocularity of two furiously staring eyes,giving way to “image of the body’s binocular vision played off against a seemingly monocular machine”.As Lobel maintains,Lichtenstein’s work of this period is marked by the tension between these two incommensurable positions:on the one hand,the idealism of unmediated vision,on the other hand,the belief that the imperfect human body prevents such transcendence.However,the latter provides a safe space for imagination away from the machine’s erasure of subjectivity[7].

8 Lichtenstein’s Apparatus

As Lobel’s research demonstrates,focusing on Lichtenstein’s concern with the mechanism of vision is a new perspective for analysing his practice.Based on this,I propose that a “virtual” observational medium is constructed through the viewer’s position and movement when observing Lichtenstein’s works.A “magnifying glass” is constructed through the Ben-Day Dots,and the enormous scale of the work,which should not be seen merely as a convention of Pop art,a form of “exaggeration,” or a sense of absurdity when compared to the original size of the appropriated objects.

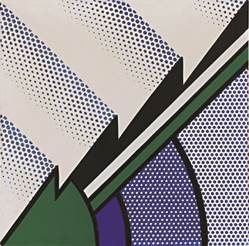

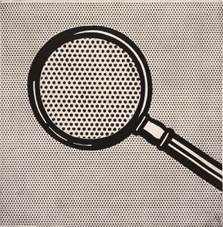

Fig.8 Roy Lichtenstein,Magnifying Glass,1963,oil and graphite pencil on canvas,412×411mm,Private collection

A person with normal vision can only see Ben-Day Dots with the aid of a magnifying glass or microscope(Lichtenstein’s 1963 work proves his awareness of this),however,almost no one would do this.In other words:our understanding of Ben-Day Dots often comes not from direct visual experience,but through popular science books,other people’s descriptions…or Lichtenstein’s works.When viewers in Tate Modern look at this four-meter-wide work from a distance,it is an enlarged comic,expanded from a small panel on prints to occupy a large amount of space in the huge gallery.At this point,the Ben-Day Dots on the painting are almost invisible and easily overlooked,just as they are in prints,but when people approach,these small dots become clear,however,the complete image is no longer visible,and only these dots fill their field of vision.

I want to use the concept of structuralist film mentioned by Krauss[4] to explain and draw an analogy with the effect brought about by the scale of Lichtenstein’s works:from a modernist perspective,film is understood as a concept of “apparatus”:the “support or medium of film” is not the celluloid film with images,not the camera that shoots them,not the projector that screens them,not the white beam of light projected by the projector,nor the screen—but the sum of all these things.Additionally,it includes the audience’s position fixed between the projector behind and the image projected ahead.As Krauss[4] proposing the goal of the structuralist film:“producing the unity of this diversified support in a single,sustained experience in which the utter interdependence of all these things would itself be revealed as a model of how the viewer is intentionally connected to his or her world”.Similarly,Lichtenstein’s work can also be understood as a kind of “apparatus”.This apparatus contains not only the form and content included in the work,but also the space in the gallery,viewer’s viewing position,the viewer’s movement during viewing,and the virtual “magnifying glass” constructed in this process.

In addition to the tension between human subjectivity and transcendence through mechanics,one of the most fundamental inspirations provided by Lichtenstein’s series on “monocularity” should also be awared of:these works highlight the act of “viewing”,making it visible.Through Joseph Vogel and Brian Hanrahan’s review of Galileo’s act of observing the moon with an astronomical telescope[23],this change in conception can be traced back to a more ancient paradigm.Vogel and Hanrahan maintain that Galileo’s telescope made the act of observation visible,“erased the coordinate of natural vision,the natural view,and the natural eye”.Since Galileo,vision can no longer be considered natural or given,visual perception is now recognised as constructed.The human eyes,have lost their status as the trustworthy instrument of Aristotelian revelation—what we see contains as much falsehood as truth.As Vogel and Hanrahan[23] advocate,the “self-referential” characters of Galileo’s telescope imply three dimensions:First,the telescopic perspective simultaneously identifies the viewer along with what is being viewed.Furthermore,when Galileo establishes a connection with his observed objects,he simultaneously creates a relationship between the observation process and itself.Lastly,the telescope’s fundamental quality as a medium manifested in this “self-referential” structure.Although Galileo’s telescope is physical and Lichtenstein’s magnifying glass is virtual,they both make the observer themselves visible,make the act of viewing visible,and simultaneously,in this process,make themselves visible,as a medium.The materiality of this magnifying glass is only established in the dynamics of the viewer’s observation.The viewer is forced to enter a field about the act of viewing,becoming a part of the “apparatus”.When this “apparatus” undermines the viewer’s subjectivity,in contrast,the artwork becomes,like the viewer,an object in the world—so does the space between the viewers and the painting.As Bolter and Grusin note,the space between the viewer and the canvas is controlled,institutionalised,and regulated as a special,real space in which people can walk or wait to enter[6].

Vilém Flusser’s theory in Line and Surface(2002)[9],which extends from “reading lines(reading words,language)” and “reading surfaces(reading images)” to “media of conceptual fiction(media of linear fiction)” and “media of imaginal fiction(media of surface fiction)”[9],undoubtedly provides a new path for understanding the enormous scale of Lichtenstein’s works and his Ben-Day Dots.Lichtenstein’s works also embody another dimension:they are not flat,but deep.

Flusser first gives an example:people can easily distinguish between a stone,the mineralogical explanation about the “stone”,and a photograph of the stone because everyone has seen stones.The photograph and the explanation are the media through which humans understand this stone.However,in daily life,most examples are not as simple as a stone:for some other concepts,when we say we “know” these concepts,we cannot determine whether they truly exist somewhere,or whether it even matters if they only exist in media.However,things like genetic information and the Vietnam War do indeed affect our lives.Therefore,as Flusser maintains,when immediate experiences are impossible,media become the actual objects of our knowledge.Media continuously expand our awareness of things which cannot be personally experienced immediately.

Subsequently,Flusser[9] continues with the stone as an example to introduce three “realms”:immediate experience(the real stone),images(photograph),concepts(explanation),and refers the realm of immediate experience as “the world of given facts”,and the realm of images and concepts as “the world of fiction”.On this basis,a key issue is raised:How does fiction relate to fact? As Flusser’s answer,fiction often pretends to represent facts by substituting for them or pointing at them through symbols.Then the question is advanced:How do the various symbols of the world of fiction relate to their meanings? In answering this question,Flusser finally returns to the concept of “line and surface” that he introduced at the beginning of his article:“written lines relate their symbols to their meanings point by point(they ‘conceive’ the facts they mean),while surfaces relate their symbols to their meanings by two-dimensional contexts(they ‘imagine’ the facts they mean…)Thus,our situation provides us with two sorts of fiction:the conceptual and the imaginal;their relation to fact depends on the structure of the medium”[9].

An example of “film and newspaper”,which is both fact and symbol,also perfectly corresponds to the state of viewing Lichtenstein’s works from different distances mentioned above,is provided by Flusser to demonstrate this distinction.If an spectator in a cinema does not accept the predetermined seat and instead presses their face against the screen,they would only see meaningless light spots,because imaginal codes,like film,are subjective.In contrast,when reading a newspaper,as long as the reader knows the meaning of the symbol,such as a letter,how the reader looks at this letter is not so important,because conceptual codes,like alphabet,are objective:as Flusser explains,“(imaginal codes)are based on conventions that need not be consciously learned…(conceptual codes)are based on conventions that must be consciously learned and accepted”.

Flusser’s following summary is what I consider the most crucial conclusion about “line” and “surface”[9] for understanding Lichtenstein’s apparatus.Draw on this,Lichtenstein’s intention in using the language(morpheme and vocabulary)of a medium(printing),the reason why Lichtenstein wanted to reproduce Ben-Day Dots,and why he used such enormous scale to make these small dots clearly visible,could be unveiled.After categorising books,scientific publications,printouts,etc.,as “media of linear fiction”,and films,TV images,and illustrated magazines,etc.,as “media of surface fiction”,Flusser first eliminates a possible misconception based on the previous example of “film and newspaper”,namely that conceptual fiction(or linear fiction)is superior to imaginal fiction(or surface fiction):people all participate in both media of linear fiction and surface fiction,but participation in the linear fiction requires learning its techniques.According to Flusser,this binary explains the division of the mass culture(people participate almost exclusively in surface fiction)and an elite culture(people participate almost exclusively in linear fiction).

With Flusser’s binary,we can finally return to the consideration of Lichtenstein’s scale dimension and Ben-Day Dots:are these dots Ben-Day Dots(or enlarged silver halide particles on a film screen,pointillist brushstrokes in Seurat’s paintings…),in other words,“imaginal points”;or they’re “morpheme” of mechanical reproduction(like Latin letters,Chinese characters…),in other words,“conceptual points”?

Therefore,should Lichtenstein’s method be considered as an act that fervently affirms the power of handcraft—mass-printed images that are only a few centimetres square can be enlarged by a hundredfold,inviting viewers,as Flusser[9] terms,to “learn how to use its techniques”,thereby gaining clarity on “the essence of mechanical reproduction”,a kind of optimism of humans against machines as Lobel[7] summarises;Or,should we see the artist’s discovery and simulation of Ben-Day Dots,the language of mechanical reproduction,as a cavalry elegy for humanity’s final,desperate pursuit for the knowability of media in the mechanical reproduction era.People straining to get close to Whaam! in Tate,just like the person Flusser describes who presses their face against the screen to see every little light spot.This epistemology will be utterly defeated before the thin red line of complete age of digitisation—there are no more Ben-Day Dots,nor silver halide particles on celluloid film.This desire for a Lichtenstein-style handcraft dissection of a mechanical medium is no longer possible.

However,as Katherine Hayles[29] points out when comparing prints and code:“an important difference between print and electronic hypertext is the accessibility of print pages compared…the words and images in the print text are immediately accessible to view…Code always has some layers that remain invisible and inaccessible to most users…print is flat,code is deep”.We can still take a step back:if we accept that Lichtenstein,by constructing a dichotomy in viewing in which “distant/close” corresponds to “the whole image(or the enlarged comic)/Ben-Day Dots”,a second dichotomy could also be constructed corresponding to an assumed differentiation between viewers who understand the artist’s intention and “tourists who focus only on appearances”.The core commonality of these two dichotomies lies in whether a viewer can recognise that “this is a comic”,“this is an enlarged comic”,“this is oil painting”,and “this is a cluster of Ben-Day Dots” are all simultaneous and contradictory.At this level,Lichtenstein’s work is not flat,but deep.If Lichtenstein questions the subjectivity of viewers through this “apparatus of viewing”,then when audiences approach closely and clearly see these Ben-Day Dots,their subjectivity is once again granted.

9 The Mechanism of Translation

If Lichtenstein’s practice had stopped at the appropriation of these mechanically reproduced images,one might can make a definitive judgment from today’s perspectives,declaring his defeat in the human versus machine confrontation.However,Lichtenstein’s later-career works(if we consider hisLandscape series from 1964 and Brushstroke series from 1965 as turning points),in some ways,anticipate the future because they incorporate a methodology of “translation”[9]:this transformation almost coincides with Flusser’s proposals and outlook.Flusser believes that linear thought should be incorporated into surface thought,concept into image,and elite media into mass media:“This development involves a problem of translation…Imaginal thought was a translation of fact into image,and conceptual thought was a translation of image into concept…” Flusser’s envisioned prospect almost exactly corresponds to today’s situation,where humans generate operational images through commands,and AI describes or processes images for humans.According to Flusser[9],the new paradigm may be like this:“imaginal thought will be a translation from concept into image,and conceptual thought a translation from image to concept…First,there will be an image of something,then there will be an explanation of that image,and then there will be an image of that explanation.”

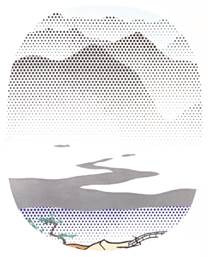

Fig.9 Roy Lichtenstein,Landscape with Silver River(1996).Acrylic,oil,graphite pencil on canvas, 2115×1692mm,Private Collection

Flusser’s concept,“translation”,is a key to understanding Lichtenstein’s later works with increased levels of figuration,such as Haystack(1968),Bull III(1973)and Still Life with Picasso(1973),in which Lichtenstein attempts to reduce famous paintings from art history into a mechanical reproduction style composed of Ben-Day Dots,flat colours and lines.One could say that Lichtenstein’s enlargement of comics,which began during World War II[7],is an attempt at reproduction and deconstruction.In this process,discovering dots and flat colours and unyielding lines already there,is the initial decoding behaviour;the early 60s work in Landscape is the place in which Lichtenstein starts the simplest encoding;then the translation of haystacks and bulls,tests and practices the reliability of this decoding-translation-encoding mechanism.In the final stage of this great Pop artist’s creative life,this mechanism,which the artist viewed as the summation of his life’s work,successfully translated another language from the East.In the series of works with Chinese painting styles created in 1996,he discovers a new usage for his “vocabulary”:using the varying density created by clusters of Ben-Day Dots of different sizes to simulate the variations in ink density in Chinese painting.①

10 Conclusion

It’s time to return to the quote from Jameson at the beginning of this paper:In the process of critiquing the myth of consumer society,a new “mythology” of appropriation art has also formed,while the myths of consumer culture seem to have become an unconquerable natural state.Perhaps artists’ exploration of media ontology,precisely because it is difficult to reconcile with the spectral recursive structure rooted in contemporary art practice and criticism,can instead become a field for generating new criticality.However,the “media turn” is not necessarily the best solution,nor the one that everyone agrees with—as Lobel somewhat ambiguously describes Lichtenstein’s work:“reminiscent of those medical treatments in which the patient is given small doses of poison in order to build up immunity”[7]—making it difficult for readers

① In Roy Lichtenstein:How Modern Art was Saved by Donald Duck,Sooke[30] mentions that Lichtenstein purchased a book on Chinese painting in London in 1944 while passing through with the U.S.Army.Sooke does not explicitly point out the clear connection between this and his series of creations in 1996,only stating “fifty years before his series of more than twenty landscapes in the manner of Song Dynasty scroll paintings.”

to determine whether this statement describes the dramatic contradiction between Lichtenstein’s mechanical reproduction language and manual crafted methods,freedom of physicality and the machine transcendence,Pop-style iconoclasm and the professional artist’s caution,or if it suggests a retreat to the realm of media(or an ascent to metaphysics)after recognising the ineffectiveness of criticism toward mass culture,with its attendant sense of loss and powerlessness.The two threads mentioned in the paper should not be viewed as having a chronological order or as situations of varying merit—that would mean the return to a kind of presupposed structuralism.What’s necessary is to re-examine and review the value of appropriation art in the post-war decades,returning it to its true historical context.In this process,the perspective of the media is not the only perspective,but one of many possible approaches.

Conflict of Interests:The author declares no conflict of interest.

[65] 通讯作者 Corresponding author:张书源,gn23924@bristol.ac.uk

收稿日期:2025-04-30; 录用日期:2025-06-24; 发表日期:2025-06-28

[66] Copyright©2020 by author(s) and Science Footprint Press Co., Limited. This article is open accessed under the CC-BY License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).